The Lessons of Hungary

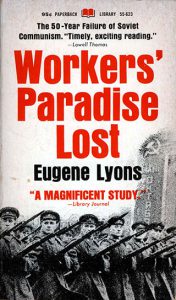

Fifty Years of Soviet Communism. A Balance Sheet (1967) 9,101 views

September 22, 2018

The present stalemate [in Russia] is so tense on both sides that it is unlikely to endure indefinitely. At some point the Kremlin will be driven to act. Either it must carry reform far beyond the present half-measures, to the degree of diluting its political monopoly, or it must again resort to terror. In either case it will be putting its survival on the line in a life-or-death gamble.

A much-quoted saying attributed to Mao Tse-tung runs this way: “In the last analysis, all the truths of Marxism can be summed up in one sentence: To rebel is justified.” But this is a concept that cuts both ways—the justification applies to communist societies no less than to others.

Mao himself learned it the hard way when his so-called cultural revolution through young Red Guards ignited a civil conflict which at this writing is still burning violently. In early 1966, the Chinese communist system seemed the most thoroughly regimented, stable, monolithic structure on this planet. A few months later, it was in flames beyond the control of the bosses, the loyalties of top mandarins and even of the army in doubt. Whatever the outcome, the events in Red China serve as a further warning against taking the “finality” of any totalitarian system for granted.

“At the top everything is peaceful and smooth, but below the top, in the depths, and even in its ranks, new thoughts, new ideas, are bubbling and future storms are brewing.” These are the words of Milovan Djilas, himself for years second in command of a communist country.

“At the top everything is peaceful and smooth, but below the top, in the depths, and even in its ranks, new thoughts, new ideas, are bubbling and future storms are brewing.” These are the words of Milovan Djilas, himself for years second in command of a communist country.

While this ferment under the monolithic surfaces was generally admitted, it had long been argued that successful revolution against totalitarian regimes is inconceivable, a thing of the past. An effective rising, it was taken for granted, calls for revolutionary organization and leadership, with an ideology or program around which the masses can be rallied—pre-conditions made impossible by the size and ubiquity of the communist police and security systems. There could be no undergrounds and conspiracies. In addition, the totalitarian tyrannies always have immense military might and the latest weapons at their disposal.

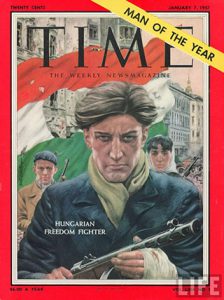

There are still a few theorists who hold this view, insisting therefore that the Soviet dictatorship can never be overthrown from within. But they can adhere to this belief only by ignoring or underrating the experience of the Hungarian revolt in October, 1956, and in lesser degree the uprisings in Poland about the same time and in East Germany in 1953. In these countries there was only negligible organized resistance, if any, and no known leadership. The rebellions were completely unexpected and spontaneous: less “movements” than explosions, unplotted, unplanned, unled, galvanized by the simplest and most basic ideas—freedom, justice, independence.

And in Hungary, it is of prime importance to recall, the revolution was successful—successful within its own frontiers, so that it could be defeated only by force from outside.

Probably modern history holds no precedent of a revolution that triumphed so overwhelmingly so quickly. Within three days after its outbreak, the power passed to the people, actively or passively supported by all social groupings. Initiated by students, poets, journalists—by the numerically small intelligentsia—it was joined almost at once by the factory workers, the peasantry, the remnants of the middle class, the armed forces, and a large part of the ruling Communist Party itself. Leadership emerged from the ranks, some of it from the liberated political prisoners. The discipline was truly remarkable; there was virtually no looting, no factional wars, no terror except against the security police.

Hungary, and this is its great historical importance, provided the proof that revolution against a totalitarian state is possible. It cancelled out the assumption that the new species of despotism, because it can prevent organization and atomize opposition, is invulnerable to the forces of internal unrest. In effect it established a new pattern, what might be called revolution by consensus, fundamentally unlike the classic examples of the French and Russian revolutions.

If and when there is a mass uprising against the Soviet regime—not a palace revolution but a true popular revolt—it may be expected to follow the lines of events in Hungary in the fall of 1956. It will come not through plotted arson but through spontaneous combustion, and its leadership will spring also from the ranks of communism and its elites, including the military. Consequently it is necessary to comprehend the major lessons of the Hungarian events—thus far the only successful revolution against a totalitarian state.

The first of these can be fairly stated as a law: When the time is ripe, when the climactic hour has struck, the size of the government’s military establishment, the number and quality of its weapons, becomes irrelevant. Hungary demonstrated that not only are the armed forces, and those who man the weapons, swept along by the national tide, but in the measure that they retain some discipline and leadership, these are placed at the disposal of the revolution.

Whether and when a real uprising on a nationwide scale will take place in the USSR is open to argument, but the magnitude and power of the Soviet military machine is no longer pertinent to the inquiry. Not the dimensions but the loyalties of the military setup will tell the story. If it sticks by the regime, even a small, old-fashioned army can crush a rebellion as effectively as a huge modern army. The larger the army, in fact, the closer it is to the people, the more likely to share its angers and aspirations. A small elite army (such as the special KGB force) may identify itself with the regime longer than the huge conscript army and may even find itself fighting the main military establishment until the issue is resolved.

Hundreds of formerly enthusiastic communists, among the two hundred thousand who fled the country, have given witness to the special disillusionment and anguish among their kind. They included men and women of high reputation and earning capacity, who had everything to gain from playing with the regime, yet found themselves sparking and leading the revolution. I have read and talked to many of them—their words seemed to echo those of the Soviet intellectuals among whom I lived in the early thirties. Again and again Soviet journalists, writers, actors who outwardly were “sincere communists,” trusted by the Kremlin and living a good life by local standards, talked to me in just that vein.

In many cases they posed for years—not only to me but, more important, to themselves—as true believers, but always a time came when the pose collapsed. Sometimes it was in vodka that they suddenly found the courage to protest their fate. More often it was some new excess of official ghoulishness that moved them to break silence. And always I knew that it was not to educate a foreigner that they risked frankness but to assuage their own inner despairs.

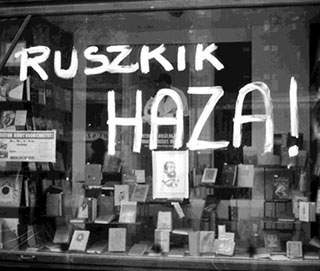

One more aspect of the Hungarian experience is particularly relevant to Soviet Russia. As you listened to or read the personal stories of escaped Freedom Fighters, in the first years after the Soviet invasion, you realized that none of them had planned to revolt or to join revolt by others. It “just happened.” Mostly they were not even conscious of being rebels, certainly not to the degree of staking their lives, until they found themselves shouting slogans and shooting guns and throwing Molotov cocktails.

An intelligent Soviet fugitive has described this phenomenon of unconscious rebellion, common to the subjects of all totalitarian states, as “double-mindedness.”

A Soviet citizen, he explained, as a matter of almost biological necessity develops two nearly unrelated minds. There is the public mind, obedient, conformist and even honestly enthusiastic for the status quo—a mind stocked with the safe slogans and doctrines. And there is the inchoate secret mind, where suppressed doubts, wrongs, resentments, and frustrations breed and fester, where dangerous knowledge and moral intuitions are filed away.

What happened in Hungary, without planning or leadership, was that the hidden mind erupted to the surface and took command. The Petőfi Circle in Budapest, where it all started, was an all-communist organization. The chain of events began with an “egghead” discussion about the role of free thought in Marxist-Leninist ideology. More and more of the participants—not against communism but in the hope of salvaging it—questioned the orthodox position and demanded a place for intellectual truth, creative freedom in the arts, exposure of faked trials. Not one of them dreamed that he was stirring up a great revolution.

The rulers and the resident foreigners and the experts were utterly astonished when the explosion came, but most astonished of all were the rebels themselves. A few apparently minor incidents crystallized the atomized resistance into a mighty unanimity. This is what can be expected in Soviet Russia, too, if and when the time is ripe. It may be touched off by student-led demonstrations of the sort that are constantly taking place; or by a mass protest against new economic burdens, such as occurred in Novocherkassk in 1962; or by some seemingly trivial episode that mysteriously, unexpectedly, lights a fuse to long-accumulated emotional dynamite.

Perhaps the greatest source of strength for the dictatorships today, in Hungary and in all communist countries, is the remembrance of the West’s failure to intervene, if only to the extent of a timely warning to Moscow not to intervene. Call it prudence or fear or a failure of nerve, the passivity of those they had accounted as friends killed the illusion among the masses and the intelligentsia that the democratic world cared and would come to their aid in case of an open conflict with the despots. The heritage of Hungary, for opponents of the task-masters in the communist world, is a bleak sense of isolation and abandonment.

In the USSR, however, this new knowledge that they stand alone is balanced in part by the realization that in the event of a revolt in Russia there will be no outside power able or willing to crush it. In theory China, if still in communist hands, might attempt a rescue operation, but practically geography is most unfavorable to such an intervention.

More than a century ago one of the most percipient of modern political thinkers, Alexis de Tocqueville, made an observation highly pertinent to the Soviet scene today:

“Experience suggests that the most dangerous moment for an evil government is usually when it beams to reform itself. … The sufferings that are endured patiently, as being inevitable, become intolerable the moment it appears that there might be an escape. Reform then only serves to reveal more clearly what still remains oppressive and now all the more unbearable; the suffering, it is true, has been reduced, but one’s sensitivity has become more acute.”

No doubt de Tocqueville had in mind the French Revolution. It erupted not when conditions were at their worst in his country but when there had been a measure of improvement portending further progress. The uprising in Red Hungary, too, came at a time when there had been some loosening of controls, a marginal but real moderation of terror. In the USSR at this writing, though no one denies that the political weather is milder, moods of discontent and protests are more open and vocal.

The so-called reforms and concessions to the people and in particular to intellectuals who reflect popular feelings may postpone a showdown with the regime—or they may provoke one. The present stalemate is so tense on both sides that it is unlikely to endure indefinitely. At some point the Kremlin will be driven to act. Either it must carry reform far beyond the present half-measures, to the degree of diluting its political monopoly, or it must again resort to terror. In either case it will be putting its survival on the line in a life-or-death gamble.