Corporate Secrecy: Read It As “Crime Inside”

December 22, 2008

War Is Crime’s note: The article below is just another example of how the allegedly “legal” veils of secrecy at a national level are used to hide the most outrageous crimes against entire humanity. Wherever in the world you live, when you see a stamp which says “Confidential” or “Top Secret,” you can bet it means “Crime Inside.”

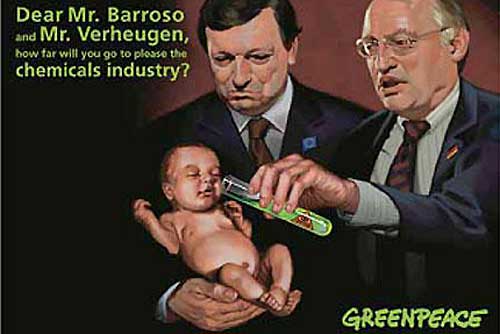

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency routinely allows companies to keep new information about their chemicals secret, including compounds that have been shown to cause cancer and respiratory problems, the Journal Sentinel has found.

The newspaper examined more than 2,000 filings in the EPA’s registry of dangerous chemicals for the past three years. In more than half the cases, the EPA agreed to keep the chemical name a secret. In hundreds of other cases, it allowed the company filing the report to keep its name and address confidential.

This is despite a federal law calling for public notice of any new information through the EPA’s program monitoring chemicals that pose substantial risk. The whole idea of the program is to warn the public of newfound dangers.

The EPA’s rules are supposed to allow confidentiality only “under very limited circumstances.”

Legal experts and environmental advocates say the practice of “sanitizing,” or blacking out, this information not only strips vital information from the public, it violates the agency’s own law.

Section 14 of the Toxic Substances Control Act, the foundation for all the EPA’s toxic and chemical regulations, stipulates that chemical producers may not be granted confidentiality when it comes to health and safety data.

“The EPA has chosen to ignore that,” said Wendy Wagner, a law professor at the University of Texas-Austin.

The newspaper’s findings are just the latest example of how EPA administrators more often than not put company interests above the needs of consumers. Over the past 18 months, the Journal Sentinel has reported on numerous EPA programs that bow to corporate pressure, frustrating health and environmental advocates and disregarding the agency’s own mission to inform the public of potentially dangerous chemicals.

The EPA has the authority to fine companies that fail to fully disclose information about dangerous chemicals. And, in at least one instance, it has done so. But critics say the program has been allowed to flounder, and the agency rarely challenges a company’s request for confidentiality.

It’s been frustrating to see the program “starved of resources and generally abandoned,” said Myra Karstadt, a toxicologist who worked on the EPA’s program from 1998 to 2005. “It’s a very worthwhile program but only if it’s given a chance to work.”

Intent was to inform

The program began 30 years ago as a way to help the public avoid contact with dangerous chemicals. The law requires companies that make chemicals to submit any information of potential hazards about their products to the EPA. The EPA, in turn, is supposed to make that information available to communities and consumers.

Companies can claim confidentiality if they are worried that their disclosures will reveal trade secrets. They have to answer 14 questions, including specifics on why disclosing the information would harm the company.

EPA administrators then decide which ones are granted confidentiality.

EPA spokesman Dale Kemery said the agency realizes the claims of confidentiality “do in some instances limit the public’s ability to understand the specifics of a particular filing.” In those cases, the agency works with the companies to get them to provide more information, which many do, he said.

But the Journal Sentinel examination of the agency’s substantial risk program found that large information gaps remain. More than half of the 32 submissions for March 2004, for example, are still missing information necessary for the public to connect the name of the chemical with the information submitted. Some have no information at all.

Consider File No. 8EHQ-0308-17103A. The EPA document, filed in March, marks as confidential the names of the chemical and the company that makes it. Even the generic class of chemical has been removed. What is the information that this unnamed company is submitting about this unnamed chemical so the public can see if it poses a substantial risk? Anxious consumers have no way of knowing.

“No information is provided in the sanitized copy of the submission,” the EPA Web site entry reads.

Hazardous if inhaled

One report, posted by an unnamed company about an unnamed chemical, shows that if the substance is inhaled, it produces “foamy macrophages” or diseased cells, in the lungs of rats. The report also indicates the chemical may cause pulmonary fibrosis – a deadly and irreversible disease in people.

There is no way to know if this is a chemical coming out of a smokestack in some town or a concern for workers at a factory. The write-up does not say where the chemical is produced or used. Nor is there any indication in the description of what this chemical is or how it works.

Another filing in May refers to a study that shows a chemical had caused liver abnormalities consistent with cancer. Again, the chemical name and any identifying information are blacked out.

“The public is being denied useful and sometimes critical information on chemical-related health and environmental hazards,” said Karstadt, the former EPA toxicologist.

Karstadt said the whole point of the program was to provide the public with information about dangerous chemicals.

“By law, health and safety data is supposed to be kept open,” she said.

The EPA’s own Web site indicates that studies, letters and accident reports are intended to be viewed by the public so citizens can “understand potential human health and environmental risks associated with exposure to chemical substances.”

The EPA posts all reports, redacted or not, on its Web site.

Oversees 28 programs

The law that requires companies to report data on dangerous chemicals is just one of 10 laws that the EPA is supposed to enforce. The office oversees 28 programs that address air pollution, water pollution, hazardous waste, toxic substances and pesticides, among other things.

The EPA is an enormous agency with three headquarters in the Washington, D.C., area and 10 regional offices all over the country. The office that administers the dangerous chemicals program has eight divisions. The overview describing their responsibilities fills 41 pages.

Even Kemery, the spokesman, could not say exactly who or how many people decide what information is allowed to be kept confidential. Nor did he know how many claims of confidentiality have been submitted and how many were granted.

The Environmental Working Group, a watchdog group based in Washington, D.C., reports that less than 1% of the EPA’s enforcement and compliance budget is spent on the Toxic Substances Control Act.

Renee Sharpe, a senior scientist with the Environmental Working Group, spent more than a year trying to get information from the EPA about some of the chemicals under the program, only to be denied at every turn.

“It’s pretty outrageous, isn’t it,” she said.

The EPA advises companies on how to keep information confidential. It is less helpful to consumers.

The information on its Web site is difficult to access. You can’t look up the chemical by name or by the name of the company that makes it. So, you have to go through the filings month by month to see if there is any information listed on that particular chemical.

There are huge gaps in reporting. The Web site does not have any information on chemicals before 2004. For reasons the EPA does not explain, the Web site does not include the second half of 2004.

That means there is no information at all about more than 16,000 entries.

Enforcement at work

Sometimes, the program works.

In 2004, the EPA fined DuPont de Nemours and Co. $10.25? million for not reporting data on Teflon. The chemical, used as nonstick coating in cookware, was found to be toxic and had been linked to birth defects. The EPA alleged that DuPont had information for more than 20 years that the chemical was harmful but did not disclose the risks.

The company agreed to settle and pay the penalty. It was the largest civil administrative penalty the EPA had ever obtained under any federal environmental statute.

Other times the EPA has encouraged companies to withdraw chemicals found to be dangerous. In 1999, 3M agreed to phase out its use of perfluorinated chemicals after discussions with the EPA. The chemicals, used in furniture coatings and to waterproof clothing, were found to cause reproductive and developmental toxicity in rats.

Still, critics including Karstadt and Wagner say the agency’s policies have grown too lax.

The real problem with the program “is a complete lack of commitment,” Karstadt said.

Even when companies say they understand the need for transparency, they aren’t always willing to provide it, the Journal Sentinel found.

Adam Bickel, manager of the Product Regulatory Center of Expertise at BASF, a major German-based chemical producer, said his company recognizes that toxic law is a “key chemical control and chemical management statute to protect human health and the environment.”

BASF is one of the companies that files the most reports to the EPA under the program. Bickel said his company takes its obligations “seriously and complies with the reporting.”

BASF submitted 101 reports to the EPA in 2008. It blacked out the chemical name in 85 of those entries.