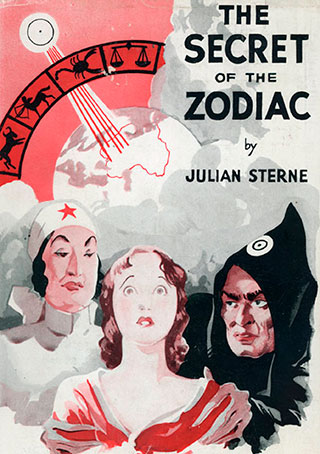

The Secret of the Zodiac: The Debacle

the book The Secret of the Zodiac (1933) 9,630 views

May 2, 2019

Early in the following year Lady Dare died of influenza, and Rosamund being left alone, Kavanagh urged that they should be married without further delay. After a quiet wedding, with only a few friends present in the church and a brief honeymoon in Portugal, they settled down in Kavanagh’s rooms in Half Moon Street and got to work again.

Early in the following year Lady Dare died of influenza, and Rosamund being left alone, Kavanagh urged that they should be married without further delay. After a quiet wedding, with only a few friends present in the church and a brief honeymoon in Portugal, they settled down in Kavanagh’s rooms in Half Moon Street and got to work again.

For Terence Kavanagh was not the man to sit down long under defeat. His resolve to stand for Parliament remained unshaken, the more so since the second National Government had failed and a General Election was to be held on the issue of Conservatism versus Socialism—unhappily with the same leaders at the head of the Conservative Party.

So, with Rosamund as his companion in arms, Kavanagh went down to South Mershire and started on a vigorous campaign against his Socialist opponent. He understood the working-class mind well enough to realise that it has no use for the compromises and concessions dear to the heart of the Intelligentsia, and his habit of hard hitting won him support on all sides. Even the people who did not agree with him respected his courage and warmed involuntarily to the fire of enthusiasm that flashed out in his speeches, whilst Rosamund’s charm and reasoned arguments ensured her a sympathetic hearing.

In spite of his secret discouragement at the inertia of his Party and the lack of support given him by its Central Office, Kavanagh fought on undismayed. He was determined that if possible there should be at least one man at Westminster who knew the truth and would have the right to tell it to the country.

But his successes evidently did not enhance his popularity in official circles. Apart from his own particular friends, he found a gulf widening around him, and the other members, when he dropped in at the Carlton Club; men who would formerly come up with a hearty, “Hullo! old chap!�? or settle down beside him for a talk, now nodded coldly or moved away if he sat down near them.

“I can’t think what’s the matter with these fellows,�? he said one day to General Brighorn, whom he had grown rather to like in spite of his crossword complex. There was something wholesome, frank, and cheery about him that gave one the feeling of sitting over an open fire and was pleasant if one happened to be feeling the draught. Besides, Brighorn was a man everybody talked to and who knew what was going on.

“I feel they’re not particularly friendly just now,�? Kavanagh went on, throwing out a feeler.

“Well, as you’ve noticed that——” the General began. Then clearing his throat he added: “I fancy it’s gone round that you’re a bit extreme, Kavanagh. Fellows don’t like that, you know. They’ve heard of course about your electioneering campaign in the Midlands and they feel you’re rather an alarmist.�?

“An alarmist! But if they knew what I know,�? said Kavanagh, “they’d jolly well realise that there’s something to be alarmed about.�? Would it be possible to confide in Brighorn and get him to help in opening the eyes of members? But no, he was too comfortable to wish to make himself unpopular.

“Oh yes, my dear fellow,�? the General was saying, “of course you and I know the dangers of the Bolshevist menace. I’ve spoken out on it loud enough myself. But when it comes to attacking the Labour Party it’s different.�?

“Is it—when we know what some of them have been plotting abroad? Besides, look at what they say themselves they’ll do if they get into power! Nationalise the land, the banks, transport, electricity, the big industries of the country as a beginning.�?

“Oh, my dear fellow,�? interrupted the General with a laugh, “they won’t really do that. They may say they will, but when it comes to the point they’ll see it’s impracticable.�?

At this moment, however, the member for Mudford claimed the General’s attention, and he turned away with evident relief to discuss the prospects of the Cambridgeshire.

“Are all these people mad, or am I?�? Kavanagh said to Brandon that evening as they sat over whiskies and sodas in his rooms. “They make one feel at times that hunting, racing, and tips on the Stock Exchange really are the only things that matter, and that one must be a crank to bother about trifles like the fate of the Empire.�?

“Well, they’ll wake up when their world comes to an end—that’s to say when the hunting’s stopped and racing is nationalised. That’s the only thing that’ll get under their skins.�?

“And by that time it’ll be too late. But it’s no good warning them. You might as well try to rouse the sleepers in an opium den. Besides, they’re perfectly convinced of getting in again with a thumping majority.�?

As the fateful date approached a certain liveliness sprang up at the Carlton Club and other haunts of the Party. For a fortnight before the day fixed for the polls, sport ceased to be the main topic of conversation, and the chances of candidates were discussed with almost the same fervour as the chances of horses hitherto. Now that the Election campaign had begun the Labour Party became fair game for attack; “personalities�? had of course to be excluded, hence no mention of the Rauschenberg pact could be made, but the published programme of the Party met with eloquent denunciations. The public, however, too long lulled to slumber, refused to be alarmed and the result of the General Election was a crushing defeat for the Conservatives. The former Prime Minister himself, Mr. Nelson Parbury, lost his seat, and the Socialist Party under George Hanley, the leader of the Left Wing, came in with an overwhelming majority.

As the fateful date approached a certain liveliness sprang up at the Carlton Club and other haunts of the Party. For a fortnight before the day fixed for the polls, sport ceased to be the main topic of conversation, and the chances of candidates were discussed with almost the same fervour as the chances of horses hitherto. Now that the Election campaign had begun the Labour Party became fair game for attack; “personalities�? had of course to be excluded, hence no mention of the Rauschenberg pact could be made, but the published programme of the Party met with eloquent denunciations. The public, however, too long lulled to slumber, refused to be alarmed and the result of the General Election was a crushing defeat for the Conservatives. The former Prime Minister himself, Mr. Nelson Parbury, lost his seat, and the Socialist Party under George Hanley, the leader of the Left Wing, came in with an overwhelming majority.

But Terence Kavanagh, to his astonishment, found himself member for South Mershire and one of the attenuated Conservative Opposition in the House of Commons.

After this events moved rapidly. The House of Lords was immediately abolished, only a handful of members going out into the Conservative lobby in protest. The rest, fearing to appear “reactionary,�? voted with the Socialists.

The Government knew better than to make the mistake of putting forward measures of internal policy that were likely to meet with hostility not only from the Opposition benches but from the country at large. Instead they proceeded to pass a single act, called the Emergency Powers Act, giving unlimited powers to the Executive to be promulgated by Orders in Council.

England thus came to be governed much as Germany was governed by Hitler after the drastic change in the Constitution which empowered him to issue decrees prepared by the Chancellor in Cabinet. Only in England this virtual dictatorship, instead of being in the hands of an ardent national patriot, was in those of a Socialist bureaucracy allied with the most implacable enemies of the country.

Their first act was to conclude an alliance between Great Britain and the Soviet Government. Their next was to abolish all titles. For the moment it was deemed advisable not to touch the Monarchy. The people so far would not stand it.

Then came the nationalisation of the banks, placing all national finance and business under the control of the Zodiac and their nominees.

Nationalisation of the land, then of mines, railways, and transport followed. Then the great industries of the country were taken over one by one and placed under “the State.�?

In vain the “possessing classes�? protested; their estates confiscated, their dividends cut off at the source by the State banks and transferred to the Exchequer, they were left without the means to make their voices heard. The former captain of industry now counted for less than the man who swept out his nationalised workshop.

In this way a perfectly bloodless revolution was accomplished.

Meanwhile unemployment had reached gigantic proportions. An attempt had been made to meet it by increased doles and by reducing hours of labour to four and finally to two a day. But owing to the slump in industry there was still not enough work to go round.

The “people,�? however, were kept happy by the decrees on “Free Transport�? and “Free Entertainment,�? enabling the “workers�?—and the “workers�? only—to be carried free by bus, tram or tube to free cinemas, theatres, football matches and greyhound races, at which, owing to the amount of leisure at their disposal, employed and unemployed alike were able to spend most of the day. The golf courses having also been nationalised, were crowded from morning till night, not only with players; and picnic parties on the greens, scattering paper bags and empty salmon tins around them, made putting more a game of chance than of skill. In London the traffic problem had become acute, for the whole proletariat being on the move at once, the streets were almost impassable and blocks lasted for half an hour at a time.

These glorious jaunts had the desired effect, and prevented any popular agitation against the passing of the Government’s final Bill, which was duly placed on the table of the House.

The debate had begun with a discussion on the situation in India, where revolt was reported to be breaking out in all directions. The small British forces still remaining faithful to the Viceroy—now only a figurehead, deprived of all real authority—had declared that they found service impossible and their numbers unequal to dealing with revolt on so vast a scale.

Kavanagh then rose to ask whether the Government was prepared at once to reinforce the troops in India and restore order before it was too late.

“The answer was in the negative.�?

The late Secretary of State for the Colonies under the Conservative Government then asked whether it was true that cables had been received from Australia and New Zealand offering help for the required reinforcement. His Socialist successor in office replied that the cables referred to had been received, but the Government did not propose to avail themselves of the help offered.

“Why? Why?�? asked a number of Conservative members.

This was the signal for the Prime Minister, George Hanley, to hurl his bombshell into the Opposition benches. With convulsed features and the light of fanaticism gleaming in his eyes, he embarked on a tirade against the iniquities of “Imperialism—the British Raj more ruthless than any Juggernaut, crushing the life out of the Indian people and battening on their life-blood.�? Then passing on to the proffered help from the Dominions, he cried:

“What are Australia and New Zealand but dependencies of that same brutal autocracy? Let them be free as India must be free, as Ireland must be free, free to work out their own destinies under guidance of the workers of each country. Away with colonies, away with the shibboleth of Dominion status! Let us declare that the British Empire is wound up and has ceased to exist!�?

Frantic applause from the Government benches greeted this speech, to which the Conservatives listened in consternation, finally breaking out into a chorus of protest.

But it was too late.

The motion put to the House three days later met with whole-hearted support from the Socialist members, who, at the division, streamed out to a man into the Government lobby.

The Bill was passed by a large majority amidst a pandemonium in which Conservative groans were drowned by the deafening cheers of their opponents.

The British Empire had ceased to exist.

***

Kavanagh, walking back to Half Moon Street as in a dream that evening, noted the posters at the street corners announcing the usual startling news: “Famous film star divorced,�? “Former Baronet at Bow Street.�? … Buying a paper he scanned the column headings. No, there was nothing yet about the debate. He turned to the stop press. Ah! there it was! Beneath the cricket scores and latest racing news, two lines of small print: “Replying to Major Kavanagh this afternoon the Prime Minister proposed the complete independence of India and the Dominions.�?

“So passes the British Empire!�? Kavanagh said aloud, crushing the paper into a ball and hurling it into the gutter.

Reaching the rooms which his salary as a legislator still allowed him to retain, Kavanagh found Rosamund busy with the scanty evening meal which, now that domestic service had been abolished, they were wont to prepare for themselves. In a few brief sentences he told her what had occurred.

“So that’s the end!�? Rosamund said blankly. “Oh, Terence, to think that everything might have been saved if only they’d have listened to you and Jimmy!�?

“Yes. It’s ghastly. But there’s no good in going over the past. We’ve got to face the future.�?

“And the only way to do that is to live by the day and hour,�? Rosamund said practically. “If only the milkman would come I’d make the coffee.�?

Under Socialism the State dairyman bringing round the blue liquid that did duty for milk was liable to arrive at any odd hour of the day or night—it all depended on when supplies arrived from the country.

“There’s a ring at the bell, perhaps that’s the milkman,�? said Kavanagh, rising and going to the door. “Hullo, it’s Jimmy! Come in, old chap.�?

Brandon, who was now earning a precarious livelihood as a State cinema decorator, entered glumly.

“You’ve heard then?�? asked Kavanagh.

Brandon nodded. The news from Westminster had reached him on his way home from work. Sitting down he took out his pipe and filled it with the rank weed supplied by the State Tobacco Company.

“Let us eat and drink for to-morrow we die!�? Kavanagh said after a long silence, with a heavy attempt at cheerfulness. “Share our orgy of macaroni and coffee substitute. We’re only waiting for the milkman, to begin.�?

“Talking of macaroni,�? Brandon answered, pulling a letter out of his pocket, “reminds me that this arrived to-day from Italy. You’d heard Countess Zapraksy died suddenly the other day?�?

“Yes. I don’t think she ever got over the shock of all that happened at Bogazzo. It must have been a terrible disillusionment to her.�?

“Well, the strange thing is, that she’s left you and me heirs to her property—the Villa Pax Mundi and quite a lot of money. This letter is from her lawyers. What are we to do about it? Go over and claim it?�?

“Yes. But we shouldn’t be allowed to bring money over here and we can’t settle at Bogazzo.�?

“No. We’re not rats to desert the sinking ship.�?

“Just so. But what about getting Rosamund out of the country?�?

“Thanks. I’m not going to be got out,�? Rosamund said firmly. “I’ll stick it as long as you both do. But there’s no reason why we shouldn’t all go to Bogazzo for a breather now and then, is there? Hullo, I believe that really is the milkman this time.�?

For a rattle of cans had sounded outside. Going to the door Kavanagh took their meagre ration of milk from the man’s hand and was surprised to hear him say:

“You don’t remember me, Major Kavanagh!�?

Where had he heard that voice before? Looking for the first time at the milkman’s face, which also seemed familiar, he answered:

“Not for the moment—and yet—and yet—is it possible that you are Mr. Parbury?�?

Mr. Parbury, shabby and haggard with a stubbly growth around his chin!

“Is it really you?�? Kavanagh repeated in astonishment.

“Yes, Nelson Parbury. Once Prime Minister of England. We little thought we should live to see this day.�?

It was almost more than Kavanagh could do not to answer: “My good Parbury, I knew it, but you would not believe me!�? But on the principle of never saying “I told you so!�? he only answered:

“Well, Mr. Parbury, I’m sorry to see you’ve come to this.�?

“Oh, I’m lucky to have a job at all,�? Mr. Parbury answered, with well-assumed cheerfulness; “it’s the news I’ve just heard from the House that’s upset me. Is it really true that they’ve wound up the Empire?�?

“Yes, only too true. You’ll see it in the papers tomorrow.�?

Mr. Parbury took out a large grey pocket handkerchief and wiped his forehead.

“The poor old Empire!�? he muttered, “the poor old Empire! To think it’s gone!�?

Shaking his head mournfully, he picked up his milk cans and went on with his rounds.

By the morning the Press had realised that something quite sensational had happened in Westminster. The Test Match was actually relegated to the fourth column, whilst leading articles and glaring headlines dealt with last night’s debate. The organ of the Socialist Party of course was jubilant, but the constitutional Press in general expressed disapprobation, rising in one or two cases to almost violent protestations—this thing must not be, the country would not stand it, etc.

But the principal daily mouthpiece of the Conservative Central Office set the example of sanity, warning the country not to give way to hysteria.

“The present situation,�? it wrote, “must be faced with calmness. Whatever sentimental regrets may be entertained at the passing of so time-honoured an institution as the British Empire, it behoves us to take a larger view than that of narrow nationalism, and to consider the welfare of the world at large. Seen from this angle the action of the Government last night was statesmanlike and far-sighted, a gesture which cannot fail to arouse admiration in every corner of the earth. Britain has shown her strength by surrendering those advantages won in the past by force and by recognising that with the advance of civilisation the word ‘Imperialism’ must be expunged from our vocabulary,�? etc., etc.

At Geneva the great news was received with acclamations, and the League of Nations, at a special meeting convened for the occasion, passed a unanimous resolution that: “The abolition of the British Empire marks the passing of Imperialism and provides the surest guarantee for the peace of the world.�? In consequence “the Disarmament Conference which has sat for ten years can now be disbanded.�?

***

Although the Empire was gone the Government still dared not touch the Monarchy, and contented itself with depriving it of all authority. The Royal Family became virtually prisoners in the Palace, as it had been in France after 1789.

It was further decided that the Soviet system should not be adopted as it was unsuited to the British people, whose individualistic character might make them less docile members of soviets (or councils) than the Russian workers. The farce of pretending to admit them to the government of the country would be quickly seen through here. Legislation was therefore carried out by the host of officials from East and Central Europe who had swarmed into the country and been placed in key positions in every sphere of distribution.

Up till this moment the orgy of free amusements and unlimited food supplies by the State from the stocks laid in by the previous Government had kept the workers quiet. But now, owing to the dislocation of industry and the decline of national credit, supplies began to fail. Rates and taxes having been abolished since there was no one left to pay them, the dole had to be done away with, and the population kept alive on rations that grew every week more meagre. An undercurrent of discontent now arose, and the sight of their new masters driving through the streets in luxurious motors with complacent smiles on their Oriental features was gradually rousing the populace to frenzy.

All pretence of Parliamentary Government was finally abandoned, for power had now passed from the hands of legislators into those of the officials who, having all the means of life under their control, were able to hold undisputed sway. The House of Commons was now closed down, and not only the Conservative but the Labour Party was “liquidated.�? In order to prevent any attempt on the part of the dismissed members to organise an Opposition outside Government circles, all those who had sat as Conservatives were banished, together with any of their supporters who were held to be dangerous enemies of the Socialist regime. On the list of exiles was found the name of James Brandon.

Forced therefore to leave the country, Brandon, together with Kavanagh and Rosamund, found a refuge in the Villa Pax Mundi, where, amidst sunshine and vineyards, they watched sadly from afar the final eclipse of the British Empire.

Others of their fellow-countrymen, less fortunate, wandered poverty-stricken about the world; there was no country to be found ready to take up the part played in the past by England towards the refugees flying from social revolution. Mr. and Mrs. Nelson Parbury, after knocking in turn at all the frontiers of Europe, and finding a welcome nowhere, were finally received unwillingly by the Eskimos.

Meanwhile, the former “Labour�? leaders who had remained in the country, found themselves reduced to the ranks, obliged to seek jobs as best they could in nationalised industry. Hanley, in despair at seeing the reality to which his dreams of a Socialist Paradise had led, flung himself into the river from Westminster Bridge.

This state of affairs was not at all to the taste of those members of the Labour Party who had fared sumptuously in the bad old days of the Capitalist system. Accordingly, Messrs. Bagnall, Pudsey, and Renton decided that the English climate was no longer suited to their health, and bethought themselves of seeking refuge with some of their friends abroad. Who would be more likely to befriend them than General von Rauschenberg whose programme they had carried out so faithfully?

One summer’s day the trio arrived in Stolzenbach and sought an early interview with His Excellency.

“So?�? he said, glaring at them from under his bushy eyebrows. “For what have you come?�?

“We have come to claim your protection. Our own country has become uninhabitable. We wish to live in Germany and to become German citizens.�?

“Germany has no use for traitors,�? answered the General, and turning to his Jäger he said abruptly:

“Take these dogs out and shoot them!�?

Which was done.

The fiery General had found out his mistake at last. Like many another Continental foe of England he began to find himself hoist with his own petard. The tide of Bolshevism which he had helped to direct against the Allies now threatened to invade his own country.

For with the downfall of the British Empire the whole structure of civilisation had been shaken to its foundations, and even those who had hated it for its greatness now trembled for their own safety. In France, Belgium, Holland, Switzerland, the Communists began to gain the upper hand. Spain declared a Soviet Republic. Japan, undermined by Bolshevist propaganda, defended itself desperately against the combined attacks of Russia and China.

In India, with the withdrawal of the British Army and Police, fierce racial riots broke out; soon it was war to the knife between the Moslems and Hindus. In Palestine, no longer under the Protectorate of Great Britain, the Arabs turned upon the Jews; in South Africa, Dutch and British settlers alike found themselves faced by a rising of the black races; the United States by an anti-Anglo-Saxon coalition of the alien elements that made up so large a proportion of their population.

The whole world rushed towards chaos.

The Revolution, like Saturn, was eating its own children. The thousands of writers, speakers, artists, propagandists, who had spent their energies in undermining the structure of civilisation, found themselves being gradually buried underneath its ruins. This was no return to Nature, no clean sweep such as they had pictured, but a squalid mess amidst which they wandered trying to pick the means of existence from beneath the wreckage. Powerful to destroy they had no conception how to set about the work of reconstruction. They had killed society and could not live upon its corpse.

Even the Zodiac had overreached itself. Events had moved too quickly for its reckonings. Accustomed to know beforehand what was going to happen and therefore how to turn everything to profit, the Twelve now found themselves unable to keep pace with the changes taking place simultaneously at all points of the globe. They had wanted revolutions, but ordered revolutions exploding like time fuses at the appointed moment. They had wanted wars, but wars carried out on fixed lines, of which they could calculate the outcome, not sporadic wars breaking out here and there like heath fires in all directions at once. They had wanted to destroy the British Empire, but only in so far as it was British, preserving the framework so that they might take it over. They did not want it reduced to scrap-iron of which no use could be made.

For the Zodiac had set out to rule the world and they had come to reign over ruins. The disciplined organisation they once held at their disposal had been broken up, their agents and agitators, formerly brigaded and prompt to obey, had been reduced to a disorderly rabble. The industries they controlled had been thrown out of gear. The spider’s web of finance they had spread out all over the world was breaking at every point. The fabulous wealth they had amassed had turned to dust; their stores of gold could purchase nothing. Of what use to Virgo were munition works, coal mines, and railways in a dozen different countries, when the workers in them could not be depended on for a moment? How was Aries to carry on his operations in Wall Street if the New York Stock Exchange had closed down? How could Scorpio reap the benefit of the boycott of British goods in the East when India and China were in a state of anarchy? How was Sagittarius to ring up Buenos Ayres if the Argentine telephone system had been put out of action that day by revolutionaries? And how were Libra, Gemini, and Aquarius to project thought over a demented multitude? The passivity on which they depended for mass propaganda had been dispelled; men were thinking at last, thinking furiously, for the day of words was done and grim realities stared them in the face.

It was then that from an obscure centre in Italy the secret of the Zodiac was broadcasted to the world; the names of the Twelve and their scheme of world power were published in a score of languages. Then the tide of human passions that the Zodiac had set in motion turned against themselves. Their agents in the Kremlin, no longer able to maintain discipline in the Red Army, were massacred by mutineers from within its ranks; peasant riots and pogroms broke out everywhere. In New York, Oscar and Isidore Franklin were lynched by a maddened crowd; in London Cancer was shot by a hungry workman; a bomb blew Pisces to bits in the streets of Cairo. Stricken with terror, Gemini swallowed poison, Aquarius blew out his brains, Libra died of shock. Gradually all the Twelve were removed from the earth’s surface. The Sun and Head of all lost his reason.

The world they left behind them was in chaos; civilisation had been set back a hundred years. But the power of the Zodiac was ended. Humanity was free to work out its own salvation.

Digital discoveries

- Migliori Casino Online

- Casino Non AAMS

- Siti Casino

- Sites De Paris Sportifs Belgique

- Tous Les Sites De Paris Sportifs Belgique

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne Belgique

- Casino En Ligne Belgique Bonus

- I Migliori Casino Online

- Non Aams Casino

- Scommesse Italia App

- Migliori Casino Online Esteri

- Paris Sportif Crypto Sans Kyc

- Site De Paris Sportif

- Sweet Bonanza Avis

- Paris Sportif Ufc

- オンラインカジノ 出金早い

- Casino Live En Ligne Français

- Site De Paris Sportifs

- Meilleurs Nouveaux Casinos En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne Français

- Casino En Ligne

- Casino Retrait Instantané

- Casino En Ligne Fiable

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne 2026

- Casino En Ligne Retrait Immédiat

- Casino Français En Ligne

- Casino Italia Non Aams

- Casino Con Free Spin Senza Deposito

- Siti Di Scommesse Non Aams

- Migliore Casino Non Aams

- Casino Online Non Aams 2026

- 토토사이트 모음

- Top 10 Trang Cá độ Bóng đá

- Casino En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne France

- Casino En Ligne Argent Réel

- Casino En Ligne Retrait Immédiat 2026

- Nouveau Casino En Ligne 2026