The Bolshevik Conspiracy

November 25, 2019

In identifying the Russian Bolsheviks, who are the masters of the Soviet Union, as the enemy, we do no more than take at face value their own declarations. The declared aim of the Bolsheviks is to achieve what they call Communism throughout the world by encouraging internal revolutions against established governments, violently conducted. Their authority for this is Karl Marx. The declared policy of the Bolsheviks is to exploit what they call revolutionary situations in other countries and support the insurgents, where it is possible, by Soviet arms, or the threat of Soviet arms. Marx said nothing about this, so they have to invoke Lenin for authority here. The declared methods whereby the Bolsheviks seek to realize their aim is by undermining the authority and stability of bourgeois governments everywhere and by every conceivable means. Since the government of a sovereign nation is for all international purposes the nation itself, these aims and methods amount to a declaration of war on non-Communist peoples everywhere. The fact that what is commonly known as warlike action may be reserved, or even not contemplated, makes no difference to the principle. War is generally held to be an extension of diplomacy; it is also an extension of Communist strategy, which may or may not be used. Lenin himself made fun of people who try to differentiate between aggressive and defensive war, and at the same time said quite unequivocally that world revolution could only ensue after a series of bloody conflicts between nations. Certainly both Lenin and Stalin have also said that there is no reason why the Communist and non-Communist systems should not live peacefully side by side. On the other hand, both have made it clear on many occasions that this ‘peaceful co-existence’ can be no more than temporary; and Stalin has quite recently stated more specifically that even in the Soviet Union the full progress from Socialism to Communism cannot be completed so long as the ‘capitalist encirclement’ exists. Sooner or later, the final clash must come. As early as 1923, at the Twelfth Party Congress, with Lenin still alive, Stalin produced a handy formula to cover any aggressive war the Soviet Union cared to undertake. As the great champion of national self-determination he was seeking to justify the then recent war against Poland; but his words also set the stage for the North Korean aggression nearly thirty years later:

‘There are cases when the right of self-determination enters into conflict with another, a higher principle, namely the right of the working-class to strengthen its régime once it has achieved power. In such a case—and this must be frankly stated—the right of self-determination cannot and must not serve as a barrier to the realization of the right of the working-class to its dictatorship. The first must yield to the second. Such was, for instance, the case in 1920, when we were forced to march on Warsaw in order to defend the power of the working-class.’

The working-class, of course, means the Russian Communist Party.

It may seem odd to call the Bolsheviks the enemy when they are so vociferous in protesting that what they want is peace. We shall examine the contemporary peace movement later under the general head of Soviet propaganda; but for the moment, taking it at its face value, it is worth pointing out its irrelevance. Apologists for the Kremlin invariably assert that all those Soviet actions which we call aggressive are really defensive actions inspired by fear. Up to a point there is some truth in this. But it begs the question.

What sort of peace does the Kremlin want? And why is it afraid? When all is said, the hunted burglar is afraid; but does his fear excuse the further crimes he commits to keep himself at liberty? Even the murderer seeks peace.

The Kremlin is afraid of its own conception of the inevitable clash. This is nothing less than fear of the consequences of its own actions. The Kremlin has taken the offensive against the established systems of the West, and it expects the West to hit back. To reduce the power of the inevitable counter-offensive it increases its onslaught and, in so doing, deepens the risk of military retaliation. This makes the Kremlin still more afraid, and so on to infinity. In a word, the fear of the Soviet government, which is genuine and obsessional, is in part the outcome of what we should call a guilty conscience—except that it runs counter to Bolshevik principles to have a conscience. It is the most difficult sort of fear to dispel, because only the possessor of it knows how deeply justified it is.

The Bolsheviks, of course, with their peculiar conception of history, do not see the picture in this light at all. We, who have an established system to defend, to retain or change in our own good time and manner, can only regard the Bolshevik attack as aggression. But they see in Lenin’s revolution and everything that followed the very reverse of aggression: they see it as a counter-attack on the entrenched positions of a conquering minority who have had things their own way for too long.

Once the conquering minority and the subject majorities were seen as classes. Now they are seen as nations.

In the days when the Bolsheviks were in exile, or forming an underground resistance to the Tsars, they developed, under Lenin, a code of behaviour. This code was not only the natural expression of a persecuted minority, which takes its weapons where it can find them; it was also the expression of a group of men who called themselves materialists and who subscribed to a materialist conception of history which taught that all values were relative and all morality the protective apparatus of a dominant class in the deadly struggle of conflicting self-interests which was the mainspring of progress. The Church, for example, with its moral code, was conjured into being to frighten the poor into proper subservience to the powerful and rich. Religion, seen as the opium of the people, was a spurious comfort for the robbed, who reconciled themselves to their miserable lot with the thought of riches laid up in heaven. Justice was the rich man’s citadel. And so on. The fact that religion, church and justice, together with the whole apparatus of law, order and morality, have all too frequently been perverted in precisely this way does not make such charges any easier to contradict, especially when they are laid by the kind of fanatic whose idea of logic leads him to believe that because all dogs have tails every animal with a tail must be a dog. Religion, morality, justice, have all been perverted to base ends, sometimes more, sometimes less; therefore they are base. Honesty and truth, so-called moral qualities, have no meaning at all except as aspects of a predatory code designed to keep down the poor. Moral values change to suit the needs of the ruling class of the moment. Thus there are no absolutes in morals. Thus, if it suits the revolutionary to exalt the lie, there can be no question of immorality. And so on.

In the days when the Bolsheviks were in exile, or forming an underground resistance to the Tsars, they developed, under Lenin, a code of behaviour. This code was not only the natural expression of a persecuted minority, which takes its weapons where it can find them; it was also the expression of a group of men who called themselves materialists and who subscribed to a materialist conception of history which taught that all values were relative and all morality the protective apparatus of a dominant class in the deadly struggle of conflicting self-interests which was the mainspring of progress. The Church, for example, with its moral code, was conjured into being to frighten the poor into proper subservience to the powerful and rich. Religion, seen as the opium of the people, was a spurious comfort for the robbed, who reconciled themselves to their miserable lot with the thought of riches laid up in heaven. Justice was the rich man’s citadel. And so on. The fact that religion, church and justice, together with the whole apparatus of law, order and morality, have all too frequently been perverted in precisely this way does not make such charges any easier to contradict, especially when they are laid by the kind of fanatic whose idea of logic leads him to believe that because all dogs have tails every animal with a tail must be a dog. Religion, morality, justice, have all been perverted to base ends, sometimes more, sometimes less; therefore they are base. Honesty and truth, so-called moral qualities, have no meaning at all except as aspects of a predatory code designed to keep down the poor. Moral values change to suit the needs of the ruling class of the moment. Thus there are no absolutes in morals. Thus, if it suits the revolutionary to exalt the lie, there can be no question of immorality. And so on.

It did, of course, suit the Bolsheviks, the persecuted minority, to exalt the lie; but because of their conception of morality it was not even incumbent upon them to plead that the means is sanctified by the end—although, so imperfect is the human mind, so human even the man who calls himself a materialist, that many of them did so, quite superfluously. Lenin, however, did not. Never once did he apologize for any of his actions. He was part of a historical drama. The part he played was the part required in the great, amoral, materialist dialectic, and, though forlorn, it had a certain grandeur.

In addition to being a born materialist, Lenin was also a born conspirator. He was also a born Russian. To be a conspiratorial Russian and a natural materialist into the bargain offers unparalleled opportunities for chicanery of every kind. Lenin made the most of them. He would have been a more impressive figure had he been a little less pleased with his own duplicity. The great Bolshevik would be, like the devil or the superman, beyond good and evil and would take no pride in his own deceit, which would be the natural air for him, as for Apollyon. Lenin, for all his gifts, was only a human being, frequently too clever by half, who, intoxicated by his own diabolism, drew attention to it on every possible occasion. Often, indeed, he put himself to great trouble to obtain through deceit what he could quickly have had for the asking.

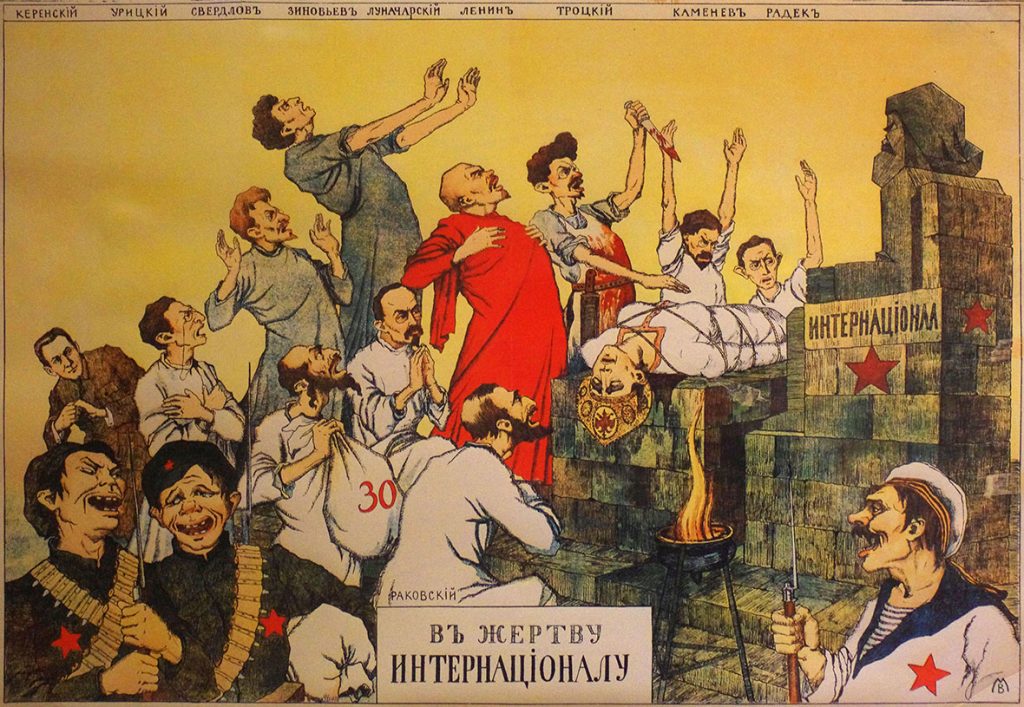

This, to return, was the atmosphere surrounding the early Bolsheviks, who, naturally, were very much conscious of their own impotence in face of the vast established order of the world, even though they told themselves that the order was doomed. The success of Lenin’s revolution was the very last thing they expected; and some of them, indeed, like the Mensheviks, were convinced that Lenin’s action was at least a generation too soon. They arrived, that is to say, in the echoing corridors of the Petrine palaces not only with blood on their hands and mud on their boots, but also with fear in their hearts and the mentality of a rather shabby secret society suddenly called upon to govern instead of to plot. For a long time, by sheer force of habit, they went on plotting—against each other, now that they were on top; against rival revolutionary parties; against the bureaucrats on whom they utterly depended. They were saved only by the convergence against them of a powerful force of anti-revolutionary Russians, backed and supported by the armies of foreign Powers. This force, like the American people to-day in their opposition to what they call Communism, was indiscriminate in its attack. It fought, that is to say, not only the Bolsheviks, who were the only serious menace to decency, but also those millions of common people who, for one reason and another, were against the return of the old régime, thus forcing them into alliance with Lenin, who offered himself as the only leader of value. During this tremendous struggle, the Bolshevik Party found its feet; and when the fighting was over and chaos and famine ruled the stricken land, there was no one to challenge them at all. They were still conspirators; but now they were conspirators on a wider front. Their conspiracy was no longer the conspiracy of a closely-articulated Party against the established order: it had become the conspiracy of a group of men against the people whom they ruled; and, on a different level, the conspiracy of one government against all other governments. The equipment the Bolsheviks brought to their conspiracies was the equipment designed to ensure the survival of a minority party of subversive fanatics and adventurers, Russians, often Jews, who had plotted fantastically the overthrow of established society in Zurich and Finsbury Circus, or preached sedition inside the Chinese wall of Tsarist Russia, all the time quarrelling bitterly among themselves—a party of Russians who had got hold of a German philosophy of history which provided the more intelligent of them with an intellectual armoury and the less intelligent with an excuse to conduct themselves like pedantic thugs and call the result historical necessity.

It was in this atmosphere that the tactics and strategy of Bolshevism were developed (and nothing is more important than to keep the tactics and strategy on the one hand, and the ultimate aims on the other, apart in one’s mind). The Bolsheviks have always thought of themselves as a minority party in bitter struggle for their existence and hated, for good reason, by the rest of the world. The senior members of the government of the U.S.S.R. cannot escape from this conception, even to-day, although they have long since grown away from their early principles. Whether the new men, who have been brought up to positions of power inside a strong Russia, are frightened to the same extent remains to be seen; but it is fair to say that the whole outlook of the Party as such, in Russia as elsewhere, is conditioned by the fact that it brings to the technique of government the lamentable tricks of the underdog. Most of its members, at the beginning, did not believe in their power. Some, like Kamenev and Zinoviev, thought they should wait for a further instalment of the Marxist cycle to unfold before they tried to seize it. Others, like Lenin, regarded the October Revolution as a rehearsal, a symbolic act on the lines of the Paris Commune, doomed in advance, but a necessary step in the Bolshevik progress. When the power which, in Lenin’s phrase, they picked up from the street after the failure of Kerensky’s government, remained with them, it seems temporarily to have misted over their appreciation of the world situation. Lenin, for example, thinking for once in terms of pure Marxism, never expected intervention by the Western Powers. When these did intervene, instead of seeing their action as the muddled, convulsive effort of a hardly pressed alliance to prevent a bunch of ragamuffins from concluding on the part of Russia a separate peace with Germany, Lenin at once knew what it was all about. This was an imperial war. Russia was the weakest link in the imperial chain, and the efforts of the allies to repair it were all part of the Marxist dialectic, as already amended by Lenin. Henceforth the capitalist powers could be relied upon to attack Bolshevik Russia by every conceivable means and on every possible occasion.

The general proposition of the proletarian revolution is based in the Marxist dialectic. In a purely material universe, the unique driving-force is self-interest. The strong, who succeed in acquiring in one way and another more of their fair share of this world’s goods, band themselves together to protect their acquisitions and so become a ruling class which sets the pattern of the whole society. All the institutions of a given society, from its church to its law, are devised more or less consciously to protect and strengthen the ruling class and exploit the oppressed classes. But nothing stands still. Everything carries within it the seeds of its own decay. The more perfectly organized the system, the more marked the internal balances and tensions. Sooner or later, acute contradictions and pressures are felt, and the existing system collapses beneath the impact of the very forces it has called into being to assist its own development. Thus, for example, the aristocratic feudal society gave way to its antithesis, the mercantile bourgeois society, which was to develop capitalism. And thus the bourgeois capitalist society must give way to its own antithesis, a society ruled by the oppressed labourers and artisans. This interplay of opposites is seen by the Marxist as an iron law of history. The proletarian society, however, is to be the final phase, the ultimate synthesis, because at last the great masses, as opposed to sectional interests, will have taken over mass control: there will then be no more classes, and therefore no more conflicts of self-interest.

Put like that, it does not sound very good. But we have to remember that Marx was writing at a moment in history when, because of the industrial revolution, the capitalists, the factory owners, were able to exploit the workers to a degree unprecedented since the days of slavery. The gulf between the conquering minority and the subservient majority had been rapidly growing; there was a revolutionary ferment in the air; and Marx saw no reason why the process should be arrested or diverted until it had ended in a smash.

He was wrong. First, for example, he failed to see that, as Professor Carr has put it, the capitalist system had created an immense network of vested interests in its own stability, the small men, who preferred to take their chance of bettering themselves inside the existing system rather than throw the system down and start again. Secondly, he failed to see that there could be no final synthesis, since, even if the proletarian revolution should take place as predicted, humanity would still be divided into the strong and the weak, who would once more range themselves into the exploiters and the exploited, as has happened in Russia since 1917. The fact remains that, his revolutionary theory apart, Marx’s thinking has deeply affected the best political and economic thinking of our time; and, paradoxically, it would have affected it a very great deal more had not a group of Russians concentrated on his revolutionary theory and deluded themselves that they had succeeded in turning it into practice.

When Lenin arrived on the scene it was obvious to anyone with a spark of commonsense that the Marxist theory of revolution had gone wrong. Lenin himself saw that something had to be done about it, and his own outstanding contribution to Marxist thought, which Stalin has inherited, was the particular proposition which laid down the way in which the proletarian revolution would be achieved.

Marx had believed that sooner or later the proletarian revolution would sweep the world. But he also believed that each country would have to produce its own revolution, which, though accelerated by the international solidarity of the working-class, could only occur at a particular point in its development and in its own way. It could never happen until a given country had been through the stage of capitalist development. The Russian Social Democrats in exile, both Bolsheviks and Mensheviks, by and large believed this: it meant in their eyes that Russia must have a bourgeois revolution before they could even begin to contemplate the proletarian revolution. This was not good enough for Lenin. Russia was admittedly at the very bottom of the list of countries ripe for proletarian revolution because she was a backward country with little capitalism, an insignificant proletariat, and a horde of illiterate peasants barely emerged from the feudal stage. Lenin had to justify within the Marxist canon the promotion of Russia to be first on the list, and so he had to extend the Marxist canon. He did this by discovering that times had changed since Marx’s day. Then the unit of capitalist society had been the self-contained bourgeois state, like Britain or Germany. Now, owing to the development of imperialism, which involved the exploitation of whole peoples by whole peoples (instead of, as hitherto, classes by classes within nations), the whole situation had altered: a capitalist state could postpone revolution at home by raising the standard of living of the masses with the fruits of colonial oppression. Lenin thus arrived at the following inspired conclusion of post hoc argument:

‘The West European capitalist countries are consummating their development towards Socialism not … by the gradual “maturing” of Socialism, but by the exploitation of some countries by others, by the exploitation of the first of the countries to be vanquished in the imperialist war (i.e., Russia) combined with the exploitation of the whole of the East. On the other hand, precisely as a result of the first imperialist war, the East has been definitely drawn into the general maelstrom of the world revolutionary movement.’

In a word, Lenin had transferred Marx’s teaching on the class-struggle, a teaching which was visibly breaking down, from the domestic to the international arena. The exploiters and exploited ceased to be classes and became nations. In so doing, he not only explained the Russian revolution (‘the snapping of the weakest link in the imperialist chain’) in quasi-Marxist terms, but he also gave the Soviet Union, as a power, as the first base of the world revolution, a pretext for intervening in the internal affairs of other powers and indulging in what Mr. Bevin has stigmatized as the most abominable international crime: the fomenting of civil wars as an instrument of policy. He not only brought Communism into Russia. Far more importantly, he brought Russia into Communism.

Digital discoveries

- Migliori Casino Online

- Casino Non AAMS

- Siti Casino

- Sites De Paris Sportifs Belgique

- Tous Les Sites De Paris Sportifs Belgique

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne Belgique

- Casino En Ligne Belgique Bonus

- I Migliori Casino Online

- Non Aams Casino

- Scommesse Italia App

- Migliori Casino Online Esteri

- Paris Sportif Crypto Sans Kyc

- Site De Paris Sportif

- Sweet Bonanza Avis

- Paris Sportif Ufc

- オンラインカジノ 出金早い

- Casino Live En Ligne Français

- Site De Paris Sportifs

- Meilleurs Nouveaux Casinos En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne Français

- Casino En Ligne

- Casino Retrait Instantané

- Casino En Ligne Fiable

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne 2026

- Casino En Ligne Retrait Immédiat

- Casino Français En Ligne

- Casino Italia Non Aams

- Casino Con Free Spin Senza Deposito

- Siti Di Scommesse Non Aams

- Migliore Casino Non Aams

- Casino Online Non Aams 2026

- 토토사이트 모음

- Top 10 Trang Cá độ Bóng đá

- Casino En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne France

- Casino En Ligne Argent Réel

- Casino En Ligne Retrait Immédiat 2026

- Nouveau Casino En Ligne 2026