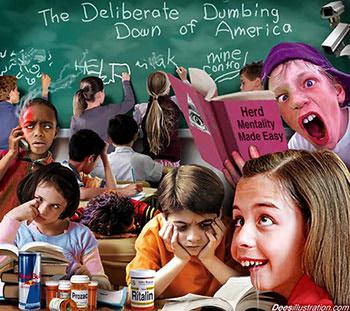

Psycho-Therapeutic Schools: Pathologizing Childhood

“There’s a tremendous push where if the kid’s behavior is thought to be quote-unquote abnormal — if they’re not sitting quietly at their desk — that’s pathological, instead of just childhood.” — Dr. Jerome Groopman, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

According to a recent report by the Centers for Disease Control, a staggering 6.4 million American children between the ages of 4 and 17 have been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), whose key symptoms are inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity—characteristics that most would consider typically childish behavior. High school boys, an age group particularly prone to childish antics and drifting attention spans, are particularly prone to being labeled as ADHD, with one out of every five high school boys diagnosed with the disorder.

According to a recent report by the Centers for Disease Control, a staggering 6.4 million American children between the ages of 4 and 17 have been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), whose key symptoms are inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity—characteristics that most would consider typically childish behavior. High school boys, an age group particularly prone to childish antics and drifting attention spans, are particularly prone to being labeled as ADHD, with one out of every five high school boys diagnosed with the disorder.

Presently, we’re at an all-time high of eleven percent of all school-aged children in America who have been classified as mentally ill. Why? Because they “suffer” from several of the following symptoms: they are distracted, fidget, lose things, daydream, talk nonstop, touch everything in sight, have trouble sitting still during dinner, are constantly in motion, are impatient, interrupt conversations, show their emotions without restraint, act without regard for consequences, and have difficulty waiting their turn.

The list reads like a description of me as a child. In fact, it sounds like just about every child I’ve ever known, none of whom are mentally ill. Unfortunately, society today is far less tolerant of childish behavior—hence, the growing popularity of the ADHD label, which has become the “go-to diagnosis” for children that don’t fit the psycho-therapeutic public school mold of quiet, docile and conformist.

Mind you, there is no clinical test for ADHD. Rather, this so-called mental illness falls into the “I’ll know it if I see it” category, where doctors are left to make highly subjective determinations based on their own observation, as well as interviews and questionnaires with a child’s teachers and parents. Particular emphasis is reportedly given to what school officials have to say about the child’s behavior.

Yet while being branded mentally ill at a young age can lead to all manner of complications later in life, the larger problem is the routine drugging that goes hand in hand with these diagnoses. Of those currently diagnosed with ADHD, a 16 percent increase since 2007, and a 41 percent increase over the past decade, two-thirds are being treated with mind-altering, psychotropic drugs such as Ritalin and Adderall.

Diagnoses of ADHD have been increasing at an alarming rate of 5.5 percent each year. Yet those numbers are bound to skyrocket once the American Psychiatric Association releases its more expansive definition of ADHD. Combined with the public schools’ growing intolerance (aka, zero tolerance) for childish behavior, the psychiatric community’s pathologizing of childhood, and the Obama administration’s new mental health initiative aimed at identifying and treating mental illness in young people, the outlook is decidedly grim for any young person in this country who dares to act like a child.

As part of his administration’s sweeping response to the Newtown school shootings, President Obama is calling on Congress to fund a number of programs aimed at detecting and responding to mental illness among young people. A multipronged effort, Obama’s proposal includes $50 million to train 5,000 mental health professionals to work with young people in communities and schools; $55 million for Project AWARE (Advancing Wellness and Resilience in Education), which would empower school districts, teachers and other adults to detect and respond to mental illness in 750,000 young people; and $25 million for state efforts to identify and treat adolescents and young adults.

One of the key components of Obama’s plan, mental health first-aid training for adults and students, is starting to gain traction across the country. Incredibly, after taking a mere 12-hour course comprised of PowerPoint presentations, videos, discussions, role playing and other interactive activities, for instance, a participant can be certified “to identify, understand and respond to the signs of mental illness, substance use and eating disorders.”

While commendable in its stated goals, there’s a whiff of something not quite right about a program whose supporting data claims that “26.2 percent of people in the U.S. — roughly one in four — have a mental health disorder in any given year.” This is especially so at a time when government agencies seem to be increasingly inclined to view outspoken critics of government policies as mentally ill and in need of psychiatric help and possible civil commitment. But I digress. That’s a whole other topic.

Getting back to young people, Dr. Thomas Friedan, director of the CDC, has characterized the nation’s current fixation on ADHD as an over diagnosis and a “misuse [of ADHD medications that] appears to be growing at an alarming rate.”

Indeed, not that long ago, the very qualities we now identify as a mental illness and target for drugging were hallmarks of the creative soul. Many of the artists, musicians, poets, politicians and revolutionaries whom we have come to revere in our society were unable to sit still, pay attention, concentrate on their work, and stay within the confines which had been set out for them in the classroom.

Visionaries as varied as Mahatma Gandhi, Richard Feynman, John Lennon, Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock, Thomas Edison, Susan B. Anthony, Albert Einstein, and Winston Churchill would have all been labeled ADHD had they been students in the public schools today. Legendary filmmaker Woody Allen claims to have “paid attention to everything but the teachers” while in school. Despite being put in an accelerated learning program due to his high IQ, he felt constrained, so he often played hooky and failed to complete his assignments. Of his school days, Gandhi said, “They were the most miserable of his life” and “that he had no aptitude for lessons and rarely appreciated his teachers.” In fact, Gandhi opined that it “might have been better if he had never been to school.”

One can only imagine what the world would have been like had these visionaries of Western civilization instead been diagnosed with ADHD and drugged accordingly. Writing for the New York Times, Bronwen Hruska documents what it was like as a parent being pressured by school officials to medicate her child who, at age 8, seemed to have “normal 8-year-old boy energy.”

Will was in third grade, and his school wanted him to settle down in order to focus on math worksheets and geography lessons and social studies. The children were expected to line up quietly and “transition” between classes without goofing around… And so it began. Like the teachers, we didn’t want Will to “fall through the cracks.” But what I’ve found is that once you start looking for a problem, someone’s going to find one, and attention deficit has become the go-to diagnosis… A few weeks later we heard back. Will had been given a diagnosis of inattentive-type A.D.H.D….The doctor prescribed methylphenidate, a generic form of Ritalin. It was not to be taken at home, or on weekends, or vacations. He didn’t need to be medicated for regular life. It struck us as strange, wrong, to dose our son for school. All the literature insisted that Ritalin and drugs like it had been proved “safe.” Later, I learned that the formidable list of possible side effects included difficulty sleeping, dizziness, vomiting, loss of appetite, diarrhea, headache, numbness, irregular heartbeat, difficulty breathing, fever, hives, seizures, agitation, motor or verbal tics and depression. It can slow a child’s growth or weight gain. Most disturbing, it can cause sudden death, especially in children with heart defects or serious heart problems.

As Hruska relates in painful detail, each time the overall effects of the drugs seemed to stop working, their doctor increased the dosage. Finally, towards the middle of fifth grade, Hruska’s son refused to take anymore pills. From then on, things began to change for the better. Will is now a sophomore in high school, 6 feet 3 inches tall, and is on the honor roll.

The drugs prescribed for Ritalin and Adderall and their generic counterparts are keystones in a multibillion dollar pharmaceutical industry that profits richly from America’s growing ADHD fixation. For example, between 2007 and 2012 alone, sales for ADHD drugs went from $4 billion to $9 billion.

If America could free itself of the stranglehold the pharmaceutical industry has on our medical community, our government and our schools, we may find that our so-called “problems” aren’t quite as bad as we’ve been led to believe. As Hruska concludes:

For [Will], it was a matter of growing up, settling down and learning how to get organized. Kids learn to speak, lose baby teeth and hit puberty at a variety of ages. We might remind ourselves that the ability to settle into being a focused student is simply a developmental milestone; there’s no magical age at which this happens.

Which brings me to the idea of “normal.” The Merriam-Webster definition, which reads in part “of, relating to, or characterized by average intelligence or development,” includes a newly dirty word in educational circles. If normal means “average,” then schools want no part of it. Exceptional and extraordinary, which are actually antonyms of normal, are what many schools expect from a typical student.

If “accelerated” has become the new normal, there’s no choice but to diagnose the kids developing at a normal rate with a disorder. Instead of leveling the playing field for kids who really do suffer from a deficit, we’re ratcheting up the level of competition with performance-enhancing drugs. We’re juicing our kids for school.

We’re also ensuring that down the road, when faced with other challenges that high school, college and adult life are sure to bring, our children will use the coping skills we’ve taught them. They’ll reach for a pill.