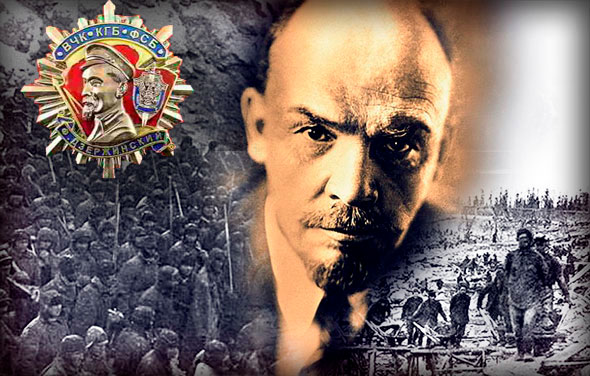

Lenin’s Gulag

September 23, 2018

The empire of concentration camps, which Solzhenitsin labeled the “Gulag Achipelago,” was not the work of Joseph Stalin, to whom it is usually attributed, but of Lenin and Trotsky. The first camps were established as early as 1918, during the Civil War. They were gradually expanded until by the early 1920’s they numbered in the hundreds. The Nazis in the early 1920’s closely observed Soviet concentration camp practices with the intention of emulating them once they came to power.

Introduction

Ever since the 1970’s when Alexander Solzhenitsyn published his Gulag Archipelago, the acronym gulag — which stands for Glavnoe Upravlenie Ispravitelno-Trudovykh Lagerei or “The Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps” — has entered the general vocabulary. There is a large literature in many languages dealing with these camps. Yet on closer inspection it turns out — with very minor exceptions — to treat exclusively with the camps installed under Stalin: those established during Lenin’s rule are generally ignored. Suffice it to say that the indexes to William Henry Chamberlin’s classic two-volume Russian Revolution, published in 1935, as well as E. H. Carr’s three-volume Bolshevik Revolution, which carries the story down to 1923, or Orlando Figes’s popular A Peoples’ Tragedy, provide no entry for concentration camps. Although it was Trotsky who introduced concentration camps to Soviet Russia, a reader will look in vain for information on this subject in his biographies, whether by Isaac Deutscher or Robert Service. Such omission is in some ways understandable since it was under Stalin that the slave labor camps reached their pinnacle, isolating and exploiting the labor of nearly three million slaves. But Soviet concentration camps first came into existence under Lenin and Trotsky. In the words of the author of an important history of these institutions:

I have … said that Trotsky and Lenin were the inventors and creators of the new form of concentration camps… I meant primarily that the Soviet Communist leaders created a defined kind of legal thinking, a network of concepts in which the gigantic system of concentration camps was latently inherent, which Stalin later merely technically organized and developed. Facing Trotsky’s and Lenin’s concentrationalism, Stalin’s concentrationalism was only a colossal consummation.[1]

There are at least two reasons why the pre-Stalin camps have been ignored by historians. One is the prevalent myth, a myth that originated with Trotsky and was formalized by Khrushchev, that in contrast to Stalin, Lenin was an intellectual who resorted to cruelty only from necessity. Hence, the camps that came into being when he run Soviet Russia were not comparable to Stalin’s. The other has to do with the scarcity of original sources. When I first interested myself in this subject I was surprised not to find any descriptions or memoirs of the Lenin camps, except for those dealing with the notorious camp at the Solovetskiy Monastery in the Far North. I knew that in 1921-22 there were in Soviet Russia some 300 such camps housing tens of thousands of inmates and yet first-hand reports of life in them were all but unavailable. I thought that perhaps I did not know where to look but then I learned that Solzhenitsyn, despite his access to the archives, was equally frustrated. This is what he wrote:

The early forced-labor camps seem to us nowadays to be something intangible. The people imprisoned in them seem not to have said anything to anyone — there is no testimony … [they] do not have a thing to say about camps. And nowhere, even between the lines, nowhere outside the text, are they implied.[2]

The reason for this puzzling lacuna eludes me to this day. And it inspires me to gather what information is available on Lenin’s camps to throw light on Stalin’s gulag, their offspring.

Concentration Camps

The expression “concentration camp” originated during the Cuban revolution against Spain in the 1890’s when the Spanish colonial power created such facilities to isolate the rebels from their families and supporters. The United States emulated them during the Philippine insurrection of 1898 as did Britain during the Boer war. But their shared name notwithstanding, these early concentration camps differed substantially from the Soviet ones in two respects: they interned foreigners, not one’s own citizens, and they were temporary military measures, installed to isolate the guerrillas from their sympathizers. The camps instituted in Soviet Russia, by contrast, were permanent, they held not foreigners but natives, and in time came to perform an important economic function by providing slave labor.[3]

Concentration camps were physical expressions of that lawlessness which Lenin proclaimed soon after seizing power. A decree issued by the Council of Peoples’ Commissars on November 22/December 5, 1917, dissolved all courts.[4] Soviet judges henceforth were to be guided by “the revolutionary conscience and the revolutionary sense of legality”: they were not bound to observe any “formal” rules of evidence.[5] Thus, in effect, Soviet Russia became a lawless country in which feelings and “conscience” rather than laws determined guilt. It remained such until 1922 when the Soviet state received its first Criminal Code. Until then (and in many respects also after then) individual Soviet citizens could be imprisoned by simple administrative procedures.

Fundamental here appears the Trotskyist-Leninist principle that every person, who somehow and for whatever reason had fallen out favor or came to be viewed unfavorably by the authorities, could be, by the simplest order, declared deprived of all rights, including the right to life, and placed outside the law.[6]

Along with the new conception of law came a new notion of morality. It was thus defined by a Cheka organ:

For us there do not, and cannot, exist the old system of morality and ‘humanity’ invented by the bourgeoisie for the purpose of oppressing and exploiting the ‘lower classes.’ Our morality is new, our humanity is absolute, for it rests on the bright ideal of destroying all oppression and coercion. To us all is permitted, for we are the first in the world to raise the sword not in the name of enslaving and oppressing anyone, but in the name of freeing all from bondage. … Blood? Let there be blood, if it alone can turn the grey-white-and-black banner of the old piratical world to a scarlet hue, for only the complete and final death of that world will save us from the return of the old jackals.[7]

The Emergence of the Gulag

The first official mention of concentration camps in Soviet Russia occurred in a statement made by Leon Trotsky, the Commissar of War, on May 31, 1918, in connection with the rebellion of the Czechoslovak Legion. Composed of pro-Allied Czech and Slovak prisoners of war who had been captured while fighting in the Austro-Hungarian army, the Legion fought alongside the Russians against the Central Powers. After the Bolshevik coup, its members were dispatched by train, fully armed, eastward with the intention of having them reach Vladivostok where they were to board ships that would carry them to France. Trotsky foolishly ordered that they be disarmed: those that refused to give up their arms were to be shot; any unit which was found to possess weapons was to be interned in a concentration camp.[8] This command was followed by several further orders in which concentration camps were mentioned. The Czechoslovaks were, in fact, not disarmed and there is no evidence that any of them were confined to camps. But the institution was mentioned for the very first time in Soviet Russia.

On August 8, 1918, Trotsky issued a directive concerning the railroad linking Moscow to Kazan, which instructed the officer in charge of this line to set up in the towns of Murom, Armavir and Sviazhsk concentration camps to confine shady agitators, counter-revolutionary officers, saboteurs, parasites, speculators, apart from those who will be executed at the location of the crime or sentenced by Military-Revolutionary Tribunals to other penalties.[9]

This command, too, was an innovation in that, for the first time in history, concentration camps were to hold not foreigners but citizens. Innovative was also Trotsky’s instruction issued in the summer of 1918 that wives and children of ex-tsarist officers mobilized in the Red Army be interned in concentration camps to serve as hostages.[10]

Lenin very early spoke of forced labor for those he considered enemies of his regime. In an article written in January, 1918, he spoke of the necessity to develop a broad diversity of methods to rid the country of “parasites.”

There must be worked out and tested thousands of forms and means of practical reckoning by the communes themselves, small cells in the village and the city. Variety is here a guarantee of vitality, a guarantee of success and the achievement of the one common goal: the cleansing of the Russian land of all harmful insects, of fleas — swindlers, of bugs — the rich, and so on and so forth.[11]

Comparisons of human beings to vermin implied their extermination. It may be noted that Hitler used similar language in regard to the Social-Democratic leaders—whom he regarded altogether as Jews — in the early 1920’s in Mein Kampf: they were “vermin” to be exterminated.[12]

A few days later Lenin wired V. A. Antonov-Ovseenko:

I welcome with my whole heart your energetic activity and merciless fight against Kaledin. I especially approve and welcome the arrest of millionaires-saboteurs in the train car of the First and Second class. I advise they be sent for half a year of compulsory work in the mines.[13]

On May 8, 1918 Lenin signed a decree calling for “the hardest forced labor” as penalty for bribery.[14] And after Trotsky had raised the issue of concentration camps, on August 9, 1918, following the rebellion of peasants in the Penza province, Lenin demanded that “ambiguous” prisoners be placed in such camps constructed outside each province’s principal city.[15]

Officially, concentration camps were established in Soviet Russia by the decree on “Red Terror” issued on September 5, 1918 following the unsuccessful attempt on Lenin’s life by Fannie Kaplan. Two days after Lenin had been shot, Yakov Peters, the Deputy Chairman of the Cheka, issued an order in which he announced that any person arrested with weapons will be shot on the spot; all who agitate against Soviet authority will be sent to a concentration camp.[16] A secret directive by the Cheka issued on September 2, 1918, ordered

1. The arrest of all prominent Mensheviks and Right SRs [Social Revolutionaries] and their confinement in prisons; 2. The arrest, as hostages, of prominent representatives of the bourgeoisie, landlords, factory owners, merchants, counter-revolutionary priests, all officers hostile to the Soviet government, and to confine this entire public in concentration camps, having set up the most reliable guard, [and] compelling these gentlemen to work under escort. In the event of any attempt to organize, to rebel, to assault the guard — execute at once.[17].

Three days later, the Council of People’s Commissars issued a resolution on “Red Terror” which declared that it was “imperative to safeguard the Soviet Republic from class enemies by isolating them in concentration camps.” [18]

On February 17, 1919, the head of the Cheka, Felix Dzerzhinsky, delivered a speech (first published in 1958) in which he said the following:

Besides sentencing by courts, it is necessary to retain administrative sentencing, namely the concentration camp. Even now the labor of prisoners is far from being utilized on public works, and I propose to retain these concentration camps to use the labor of prisoners, gentlemen who live without occupation, those who cannot work without a certain compulsion, or, if we talk of Soviet institutions, then here one should apply this measure of punishment for unscrupulous attitude to work, for negligence, for lateness, etc. With this measure we can pull up even our own workers.[19]

That day, the Cheka was authorized to commit people to concentration camps.[20] A decree dated May 17, 1919, commanded that every provincial city was to have a concentration camp capable of holding no fewer than 300 inmates; uyezd (county) towns could also establish such camps.[21]

Concentration camps soon sprouted all over the country.[22]

| Camps | Inmates | |

| 1 January 1920 | 34 | 8,660 |

| 1 January 1921 | 107 | 51,158 |

| 1 September 1921 | 117 | 60,457 |

| End of 1921 | 267 | 73,194 |

| 1 October 1922 | 132 | 68,297 |

| October, 1923 | 355 | c. 70,000 |

Russians were interned in these places of confinement by administrative procedure, i.e. without trial. In tsarist times this procedure was commonly employed to send perceived opponents into exile but never to commit them to hard labor or katorga.

A variety of facilities were used to house the prisoners, including tsarist prisons, but the majority were accommodated in monasteries and cloisters, whose previous occupants had been evicted.

The administration of the concentration camps shifted frequently between the secret police (Cheka), the Commissariat of Justice, and the Commissariat of the Interior.[23]

From the beginning, it was a principle that the concentration camps or camps of forced labor — the two terms were used interchangeably — had to be self-supporting. A decree issued by the Commissariat of Justice on January 24, 1918 ordered that all able-bodied prisoners had to engage in labor, but that this labor must not exceed in hardship (tiagost’) that expected of a free manual laborer. For this, the inmates were to be paid.[24] On May 12, 1919, it was ordained that Soviet institutions, and they alone, had the right to request the labor of camp inmates.[25]

Solovki

Early on, the main site of forced labor was established in the far north, near the port city of Archangelsk, principally on the Solovetskiy Island, officially labelled “Northern Camps of Special Designation,” or SLON. “Solovki,” as it was popularly known, had been the locale of an ancient monastic complex, used since the fifteenth century as a place of exile. An island some 25 kms long and 16 kms wide, it was heavily forested. Winter here lasts some 7-8 months during which the temperature drops to 40-45 degrees below zero Fahrenheit. During this time, the island is cut off from the mainland. In summertime, which extends for some two or two and a half months, boats would ply between the port-city of Kem, the railroad terminal from Moscow, and Solovki.

The first northern concentration camp was established at Kholmogory, a small town some 50 miles south of Archangelsk. Here were interned captured White officers as well as rebellious sailors from Kronstadt, both considered “counter-revolutionaries.” Dzerzhinsky wanted to imprison the arrested Kronstadt sailors in the Crimea and the Caucasus but Lenin decided it would be “more convenient” to intern them “somewhere in the north.” [26] Although formally Soviet Russia had nothing resembling German extermination camps (Vernichtungslagern), Kholmogory was in effect such a camp. After February 20, 1920, when units of the Red Army arrived here, there began mass executions of White officers — in late fall 1920, over 3,000 of them were shot — and mutinous sailors from Kronstadt: it was reported that in late 1922, two thousand sailors were executed in three days, and their bodies left to rot.[27] In all, during 1921-22, 25,640 inmates were shot here.[28]

In the summer of 1923, Solovki became a major center of compulsory hard labor. On July 1, 1923,there arrived by boat 175 prisoners, previously confined in the Pertominsk concentration camp, near Archangelsk. The latter camp was shut down.[29] From then on, there was a steady flow of prisoners here from jails and camps in Russia. They were divided into three groups.

The most privileged were the so-called “politicals,” mainly Social-Democrats (Mensheviks) and Right Socialists-Revolutionaries who had not engaged in subversive activity but were thought best isolated from the population at large. Numbering some 300, they were housed in a separate two-story building which had once belonged to the Savvateyevsky skete. Later on, when this building could no longer accommodate all the political prisoners, they were also quartered in two neighboring sketes. The politicals were not guarded and allowed to govern themselves by electing their headmen (starosty). They had electric light and a library, they could receive mail and publications from the mainland. They were well fed, and supplemented their diet with packages from home. Occasionally, they could have visits by relatives. This privileged status is attributable to the fact that political inmates had friends and colleagues in Western Europe whose support was important to the communists. They also could count on the sympathy of those of their colleagues who had joined the Communist Party and served in the Soviet government. In addition, they enjoyed the backing of an International Committee for Political Prisoners chaired by Roger N. Baldwin, a prominent pacifist, communist sympathizer and cofounder of the American Civil Liberties Union, an organization which included such well-known public figures as Clarence Darrow, Eugene V. Debs, Felix Frankfurter, S. E. Morison, and Norman Thomas.

In December, 1920, the head of the Cheka, Felix Dzerzhinsky and another important Cheka functionary, Martin Latsis, issued an instruction on the treatment of political prisoners:

… These categories of persons should be regarded not as people undergoing punishment but as people temporarily isolated from society in the interests of the Revolution and their conditions of detention should not bear a punitive character.[30]

On the whole, this principle was enforced but it was violated on one occasion. On December 19, 1923, camp authorities informed the political prisoners — without providing a rationale — that henceforth they would not be permitted to take outdoor walks between 6pm and 9am. The inmates protested this order and refused to obey it, whereupon the guards opened fire, killing 6 and wounding 3.[31] In protest, the inmates went on a hunger strike.[32] When the information about this massacre reached the West, there were loud denunciations: in Paris, socialist workers held a meeting on March 3, 1924, to protest the massacre.[33] In June, 1925, yielding to their demand, the political prisoners were removed to the mainland, and on the island remained only the so-called counter-revolutionaries and criminals.[34]

The next groups in terms of privileged status were common criminals. One of Marx’s less clever notions was the conviction that crime was the result of capitalism which meant that criminals should be viewed as victims and, as such, rehabilitated rather than punished. Lenin adopted this view.

Criminals confined to Solovki and colloquially known as shpana were supposed to engage in physical labor but in fact managed to avoid it. They were expected to keep an eye on the lowest stratum of prisoners, the counter-revolutionaries, whom they robbed and exploited with impunity.

The counter-revolutionaries, or kaery as they were popularly known, consisted of individuals who had actively fought the Soviet regime: White officers who had escaped the massacres and members of non-socialist political parties, tsarist officials as well as clergy. They were poorly fed and hungry most of the time. Although in theory they were to labor physically reasonable hours, in fact they worked 12 and even 14 hours cutting lumber and extracting peat seven days a week, with no time off for holidays.[35] A high proportion of them was ill with tuberculosis.

The most exhausting work is fetching wood in winter. … You stand up to your knees in snow, so that it is difficult to move. Huge tree-trunks, cut away with axes, fall on the prisoners, sometimes killing them on the spot. Clad in rags, with no mittens, with only bast shoes on your feet, hardly able to stand for weakness caused by undernourishment, your hands and whole body are frozen stiff in the bitter cold.[36]

The minimum output required was for a team of four prisoners to cut, split and pile 8 ½ cubic meters of lumber; till that was done, they could not return to their quarters.[37] The quotas set for peat extraction were also very high.[38] No mercy was shown to laggards. “At the end of winter of 1925,” recalled a survivor,

I witnessed the following incident: one of the inmates, an ill old man belonging to the “counter revolutionaries,” shortly before the cessation of work, completely lost his strength, fell into the snow and with tears in his eyes said he was unable to work anymore. One of the escorts at once cocked the trigger and shot him. The corpse of the old man was for a long time not removed in order “to frighten other sluggards.” [39]

Much of the lumber exported by the Soviet Union later on came from forced labor camps, but this fact was not publicized even in American official organs.[40] Although the forced labor in the camps during the 1920’s contributed little to the Soviet economy, it set a pattern which assumed massive proportions in the 1930’s and afterwards.[41]

The guards at Solovki consisted mainly of Chekists who had fallen afoul of the law:

One main thing which distinguishes this place of exile [Solovki] from the mines of Siberia of Tsarist days is the fact that every official in the place, from the highest to the lowest (the commander alone excepted), is an ex-criminal of the ordinary type, himself engaged in serving a term of detention. And this choice body of officials consists mostly of Che-Ka employees who have been convicted of peculation or extortion or assault or some other offense against the ordinary penal code. But, removed from all social and legal control as they are here, these “trusted workers of the State” can do what they like, and hold at their mercy the entire establishment. For the prisoners have no power of complaint — they have, as a matter of fact, no right of complaint, but must walk hungry and naked and barefooted at their guardians’ will, and work for fourteen hours out of the twenty-four, and be punished (even for the most trivial offenses) with the cudgel or the lash, and thrust into cells known as ”stone pockets,” and exposed, without food or shelter, to attacks of mosquitoes in the open. … What affects the prisoners most is not the actual conditions of the place, but the knowledge that always, for the eight months of the year, life will have to be dragged out in complete isolation from the rest of the world.[42]

It was virtually impossible to escape from Solovki: the first prisoner to reach the West and describe it, the Ingush Sozerko Malsagoff, the author of An Island Hell: A Soviet Prison in the Far North, actually fled from the mainland transit point at Kem, and reported not his own experiences but what he had heard from Solovki inmates.[43] Punishments for attempted flight were severe: any attempt to do so caused the prisoner’s sentence to be multiplied tenfold; a second attempt could result in death by firing squad.[44] The Solovki prisoners feared being shot by their guards on the pretext that they had tried to escape, and in at least one instance asked that when they were being moved their hands be bound so that they could not be accused of trying to flee.[45] Even so, throughout the country escapes from concentration camps were frequent: between January and October, 1921 there were 2,762 escapes, and during the three summer months of 1922, 6,882. Most successful escapes occurred while prisoners were performing work outside their camp.[46]

It was virtually impossible to escape from Solovki: the first prisoner to reach the West and describe it, the Ingush Sozerko Malsagoff, the author of An Island Hell: A Soviet Prison in the Far North, actually fled from the mainland transit point at Kem, and reported not his own experiences but what he had heard from Solovki inmates.[43] Punishments for attempted flight were severe: any attempt to do so caused the prisoner’s sentence to be multiplied tenfold; a second attempt could result in death by firing squad.[44] The Solovki prisoners feared being shot by their guards on the pretext that they had tried to escape, and in at least one instance asked that when they were being moved their hands be bound so that they could not be accused of trying to flee.[45] Even so, throughout the country escapes from concentration camps were frequent: between January and October, 1921 there were 2,762 escapes, and during the three summer months of 1922, 6,882. Most successful escapes occurred while prisoners were performing work outside their camp.[46]

The prisoners subsisted on starvation diets. At the Kholmogory and Pertaminsk camps they received one potato for breakfast, a soup made of potato peelings for dinner, and a potato for supper.[47] In 1921-22, as the food situation in Soviet Russia deteriorated dramatically due to the draught which inflicted starvation on millions of Russians, they had to live on one-half or even one-quarter pound of bread; in the northern camps, about 27 percent of the inmates received less than 1,000 calories a day.[48] Overworked and undernourished, the inmates of camps fell into a kind of stupor.

The detainees had no idea how long they would be imprisoned or indeed whether they would be let go, kept in confinement or shot: “for this reason, the prisoner … as if play[ed] a lottery, the stake of which was his life.”[49] The intellectuals among the counter-revolutionaries lived in such desperate conditions that some of them even unlearned how to write.[50]

When the need arose, resort was had to temporary concentration camps. Thus, during the peasant rebellion led by Alexander Antonov in the Tambov province in 1920-21, General Tukhachevsky who was in charge of government forces, set up eleven such facilities to isolate families — both grown-ups and children — from the rebels, much as the Spaniards, Americans and British had done in their colonies. They were primitive camps, not much more than “army issue tents surrounded by wire fencing.” In August, 1921, they held over 15,000 persons. Many of the detainees worked outside the camp, performing such labor as snow clearance and road maintenance.[51]

As it turned out, the majority of the inmates of Lenin’s prisons and concentration camps were not “parasites” of the leisure class or “gentlemen who live without occupation” but ordinary peasants and workers, a fact confirmed by Dzerzhinsky.[52] According to the available evidence, in November, 1920 they constituted 73 percent of the prisoners.[53]

For all the cruelty to which inmates were subjected in concentration camps, for overwork and undernourishment, in a way confinement to them was a kind of favor since the alternative was death by shooting.

Nazis Emulate

If Stalin’s concentration camps were modeled on those established by Lenin and Trotsky, so were those set up by the Nazis. As early as March 13, 1921, Hitler wrote: “When necessary, one prevents the Jews from undermining our people by interning their instigators in concentration camps.” [54] On December 8 of that year, he said in speech that when in power he would institute concentration camps.[55] Himmler, who after Hitler’s ascent to power was placed in charge of security, was well acquainted with Soviet practices:

It has been possible recently to prove that Himmler was one of earliest and best experts on Soviet labor camps. … He studied closely the Soviet institutions, which at the time hardly anyone in Germany knew, and copied many of their features. Apart from the creation of a class of slaves out of the expellees, the exploitation of their labor up to the point of delayed death, the punishment as the sense of an essentially purely mercantile organization, the supervision of the “politicals” by the “criminals” for the purpose of better spying and guarding the internal tensions among prisoners — we find all these features of Nazi concentration camps in the system of Soviet labor camps, which in this case, for once, can truly claim priority for themselves.[56]

Disbelief

The Soviet authorities did not like to admit publicly that they had concentration camps: thus the Large Soviet Encyclopedia defined concentration camps as special places of confinement, “created by Fascist governments in Germany, Poland, Austria etc.” [57] “Progressive” opinion in the West agreed with this definition. When Isaac Don Levine, the Russian-born American journalist asked a number prominent intellectuals in the West to comment on the evidence of Soviet concentration camps collected in the volume Letters from Russian Prisons, published in 1925, few bothered to reply. Some were appalled by this information. But not all. Romain Rolland, the French author of Jean-Christophe, replied that “one wrings one’s hands in disgust,” yet almost identical things were going on “in the prisons of California, where they are martyrizing the workingmen of The International Workers of the World.” Upton Sinclair professed shock to learn that Soviet prisons resembled Californian ones. Not to be outdone, Bertrand Russell expressed the hope that the publication of documents on Soviet penitentiaries “will contribute towards the promotion of friendly relations” between Soviet and western governments.[58]

The author retains the copyright of this article.

references

[1] Andrzej J. Kamiński, Konzentrationslager 1896 bis heute: eine Analyse (Kohlhammer, Stuttgart, 1982), 82.

[2] Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago, III-IV (New York, 1975), 15.

[3] Richard Pipes, The Russian Revolution (New York, 1990), 832-833.

[4] Dekrety sovetskoi vlasti, I (Moscow, 1973), 124-126.

[5] Ibid,, 469.

[6] Kamiński, Konzentrationslager, 78.

[7] Krasniy mech (Kiev), No. 1, August 18, 1919, 1; cited in: George Leggett, The Cheka: Lenin’s Political Police (Oxford, 1981), 203.

[8] L. Trotsky, Kak vooruzhalas’ revoliutsiya, I (Moscow, 1923), 214.

[9] Izvestia, No. 171, August 11, 1918; cited in: Trotsky, Kak srazhalas’ revoliutsiya, I, 232-33.

[10] Mikhail Geller, Kontsentratsionny mir i sovetskaya literatura (Moscow, 1996), 43.

[11] V. I. Lenin, Polnoye sobraniye sochineniy, Vol. 35, 5th ed. (Moscow, 1962), 204.

[12] Kamiński, Konzentrationslager, 86.

[13] Lenin, Polnoye sobraniye sochineniy, Vol. 50, 21-22.

[14] Geller, Kontsentratsionny mir, 20.

[15] Lenin, Polnoye sobraniye sochineniy, Vol. 50, 143-44.

[16] Izvestia, No. 188/452, September 1, 1918, p. 3.

[17] A. I. Kokurin and N. V. Petrov, eds., Gulag: 1917-1960 (Moscow, 2000), 14.

[18] Ibid., 15; Dekrety sovetskoi vlasti, III (Moscow, 1964), 291.

[19] Istorichesky Arkhiv, No. 1 (1958), 10.

[20] Dekrety sovetskoi vlasti, IV, (Moscow, 1968), 401.

[21] M. Losev and G. I. Ragulin, eds., Sbornik normativnykh aktov po sovetskomu ispravitelno-trudovomu pravu (1917-1959) (Moscow, 1959), 33.

[22] Leggett, The Cheka, 178; Tiuremnoe delo v 1921 g. (Moscow, 1921), 8; N. V. Upadyshev, Gulag na Arkhangelskom severe: 1919-1953 gody (Arkhangelsk, 2004), 20; Kamiński, Konzentrationslager, 86; Michael Jakobson, Origins of the Gulag (Lexington, KY, 1993), 24. Somewhat different figures are given by Galina Ivanova in Labor Camp Socialism (Armonk, N.Y., 2000), 13.

[23] These administrative shifts are described in Jacobson’s Origins of the Gulag.

[24] Kokurin and Petrov, Gulag, 14.

[25] Dekrety, V, (Moscow, 1977) 17.

[26] Richard Pipes, Russia under the Bolshevik Regime (New York, 1994), 3.

[27] S. A. Malsagoff [Sozerko Malsagoff], An Island Hell: A Soviet Prison in the Far North (London, 1926), 46.

[28] Y. V. Doikov in Otechestvenniye Arkhivy, No. 1 (1994), 79.

[29] Sotsialisticheskiy vestnik, No. 14/60, August 16, 1923, p. 15, and No. 17-18/63-64, October 1, 1923, p. 1.

[30] Leggett, The Cheka, 321, citing M. Latsis, Chrezvychainiye kommissii po borbe s kontrrevoliutsiey (Moscow, 1921).

[31] Letters from Russian Prisons (New York, 1925), 201-4; Sotsialisticheskiy vestnik, No. 4/74, February 25, 1924, 1-2, 15.

[32] G. M. Ivanova, Istoriya GULAGa: 1918-1958 (Moscow, 2006), 151.

[33] Sotsialisticheskiy vestnik, No. 6/76, March 24, 1924, 13.

[34] Upadyshev, Gulag, 23; A. Melnik and others in Zvenya, No. 1 (1991), 311.

[35] A. Klinger, “Sovetskaya katorga,” Arkhiv russkoi revoliutsii, XIX (1928), 180.

[36] Malsagoff, An Island Hell, 156.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Klinger in Arkhiv russkoi revoliutsii, 180.

[39] Ibid., 181.

[40] See, for example, U.S. Department of Commerce, The Forest Resources and Lumber Industry of Soviet Russia, Trade Information Bulletin No. 798 (Washington, D.C., 1932).

[41] Ivanova, Labor Camp Socialism, 70.

[42] Sergey Melgounov, The Red Terror in Russia (Westport, CT, 1926), 241-42, citing Revoliutsionnaya Rossiya, No. 31.

[43] London, 1926. But David J. Dallin and Boris I. Nicolaevsky, Forced Labor in Soviet Russia (New Haven, 1947), 169, are wrong in asserting that no one had ever fled Solovki: in the year following October 1926, 12 prisoners managed to escape the island: Upadyshev, Gulag, 23.

[44] Dekrety, V, 180.

[45] Geller, Kontsentratsionnyi mir, 72.

[46] RSFSR, Tiuremnoe delo v 1921 godu (Moscow, 1921), 5; N. G. Okhotin and A. B. Roginsky, eds., Sistema ispravitelno-trudovykh lagerei v SSSR (1923-1960) (Moscow, 1998), 14.

[47] Malsagoff, An Island Hell, 44.

[48] Okhotin and Roginsky, Sistema, 14.

[49] F. Dan, Dva goda skitaniy: (1919-1921) (Berlin, 1922), 179.

[50] Klinger in Arkhiv russkoy revoliutsii, 186.

[51] Eric C. Landis, Bandits and Partisans (Pittsburgh, 2008), 241-52, 352.

[52] In January, 1921: Istoricheskiy Arkhiv, No. 1 (1958), 13.

[53] Jakobson, Origins, 51. Under tsarism, peasants also constituted the majority of the prison population: Ibid., 10.

[54] Eberhard Jackel, Hitlers Weltanschauung (Tubingen, 1969), 65.

[55] Kamiński, Konzentrationslager, 83.

[56] Joachim Guenther in Deutsche Rundschau, No. 3 for 1950, 182-83.

[57] Bolshaya Sovetskaya Entsiklopediya, Vol. 34 (Moscow, 1937), 176.

[58] Letters from Russian Prisons, 12, 15, 13.

Digital discoveries

- Migliori Casino Online

- Casino Non AAMS

- Siti Casino

- Sites De Paris Sportifs Belgique

- Tous Les Sites De Paris Sportifs Belgique

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne Belgique

- Casino En Ligne Belgique Bonus

- I Migliori Casino Online

- Non Aams Casino

- Scommesse Italia App

- Migliori Casino Online Esteri

- Paris Sportif Crypto Sans Kyc

- Site De Paris Sportif

- Sweet Bonanza Avis

- Paris Sportif Ufc

- オンラインカジノ 出金早い

- Casino Live En Ligne Français

- Site De Paris Sportifs

- Meilleurs Nouveaux Casinos En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne Français

- Casino En Ligne

- Casino Retrait Instantané

- Casino En Ligne Fiable

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne 2026

- Casino En Ligne Retrait Immédiat

- Casino Français En Ligne

- Casino Italia Non Aams

- Casino Con Free Spin Senza Deposito

- Siti Di Scommesse Non Aams

- Migliore Casino Non Aams

- Casino Online Non Aams 2026

- 토토사이트 모음

- Top 10 Trang Cá độ Bóng đá

- Casino En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne France

- Casino En Ligne Argent Réel

- Casino En Ligne Retrait Immédiat 2026

- Nouveau Casino En Ligne 2026