How America Took Up Where Russia Left Off

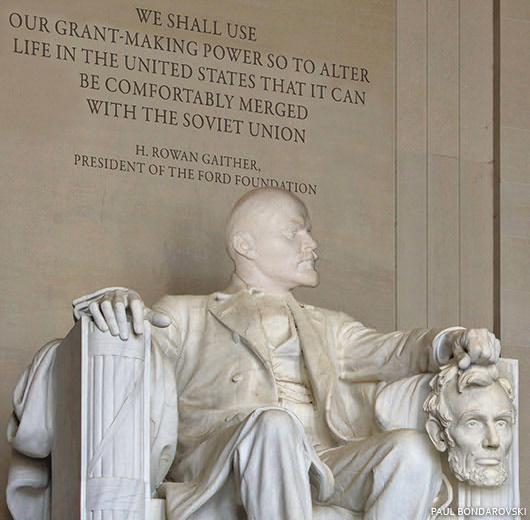

“We shall use our grant-making power so to alter life in the United States that it can be comfortably merged with the Soviet Union.” — H. Rowan Gaither, President of the Ford Foundation.

The testimony you are about to read represents a missing piece in the puzzle of modern history. It shows how the tax-exempt foundations of America since at least 1945 have been operating to promote a hidden agenda which has nothing to do with the surface appearance of charity or philanthropy. The real objective has been to condition Americans to accept the creation of world government based on the principle of collectivism, which is another way of saying socialism or communism.

The testimony you are about to read represents a missing piece in the puzzle of modern history. It shows how the tax-exempt foundations of America since at least 1945 have been operating to promote a hidden agenda which has nothing to do with the surface appearance of charity or philanthropy. The real objective has been to condition Americans to accept the creation of world government based on the principle of collectivism, which is another way of saying socialism or communism.

The man who tells this story is Mr. Norman Dodd, who in 1954 was the staff director of the House Special Committee to Investigate Tax-Exempt Foundations and Comparable Organizations, or more popularly the Reece Committee, in recognition of its chairman, B. Carroll Reece. The interview was conducted by G. Edward Griffin in 1982.

Ed Griffin: Mr. Dodd, let’s begin this interview with a brief statement. For the record, please tell us who you are, what is your back- ground and your qualifications to speak on this subject.

Norman Dodd: Well, Mr. Griffin, as to who I am, I am just, as the name implies, an individual born in New Jersey and educated in private schools, eventually in a school called Andover in Massachusetts and then Yale university. Running through my whole period of being brought up and growing up, I have been an indefatigable reader. I have had one major interest, and that was this country as I was lead to believe it was originally founded.

I entered the world of business knowing absolutely nothing about how that world operated, and realized that the only way to find out what that world consisted of would be to become part of it. I then acquired some experience in the manufacturing world and then in the world of international communication and finally chose banking as the field I wished to devote my life to.

I was fortunate enough to secure a position in one of the important banks in New York and lived there. I lived through the conditions which led up to what is known as the crash of 1929. I witnessed what was tantamount to the collapse of the structure of the United States as a whole.

Much to my surprise, I was confronted by my superiors in the middle of the panic in which they were immersed. I was confronted with the question: “Norm, what do we do now?” I was thirty at the time and I had no more right to have an answer to that question than the man in the moon. However, I did manage to say to my superiors: “Gentlemen, you take this experience as proof that there’s something you do not know about banking, and you’d better go find out what that something is and act accordingly.”

Four days later I was confronted by the same superiors with a statement to the effect that, “Norm, you go find out.” And I really was fool enough to accept that assignment, because it meant that you were going out to search for something, and nobody could tell you what you were looking for, but I felt so strongly on the subject that I consented.

I was relieved of all normal duties inside the bank and two and a half years later I felt that it was possible to report back to those who had given me this assignment. And so, I rendered such a report. And, as a result of the report I rendered, I was told the following: “Norm, what you’re saying is we should return to sound banking.” And I said, “Yes, in essence, that’s exactly what I’m saying.” Whereupon I got my first shock, which was a statement from them to this effect: “We will never see sound banking in the United States again.”

They cited chapter and verse to support that statement, and what they cited was as follows: “Since the end of World War I we have been responsible for what they call the institutionalizing of conflicting interests, and they are so prevalent inside this country that they can never be resolved.”

This came to me as an extraordinary shock, because the men who made this statement were men who were deemed as the most prominent bankers in the country. The bank of which I was a part, which I’ve spoken of, was a Morgan bank and, coming from men of that caliber, a statement of that kind made a tremendous impression on me. The type of impression that it made on me was such that I wondered if I, as an individual and what they call a junior officer of the bank, could with the same enthusiasm foster the progress and policies of the bank. I spent about a year trying to think this out and came to the conclusion that I would have to resign.

I did resign, and, as a consequence of that, had this experience. When my letter of resignation reached the desk of the president of the bank, he sent for me, and I came to visit with him, and he stated to me: “Norm, I have your letter, but I don’t believe you understand what’s happened in the last ten days.” And I said, “No, Mr. Cochran, I have no idea what’s happened.” “Well,” he said, “the directors have never been able to get your report to them out of their mind, and, as a result, they have decided that you as an individual must begin at once and you must reorganize this bank in keeping with your own ideas.” He then said, “Now, can I tear up your letter?” Inasmuch as what had been said to me was offering me, at the age of by then thirty-three, about as fine an opportunity for service to the country as I could imagine, I said yes. They said they wished me to begin at once, and I did.

Suddenly, in the span of about six weeks, I was not permitted to do another piece of work and, every time I brought the subject up, I was kind of patted on the back and told, “Stop worrying about it, Norm. Pretty soon you’ll be a vice president, and you’ll have quite a handsome salary and ultimately be able to retire on a very worthwhile pension. In the meantime you can play golf and tennis to your heart’s content on weekends.” Well, Mr. Griffin, I found I couldn’t do it. I spent a year figuratively with my feet on the desk doing nothing, and I couldn’t adjust to it, so I did resign and, this time, my resignation stuck.

Then I got my second shock, which was the discovery that the doors of every bank in the United States were closed to me, and I never could again get a job, as it were, in the banks. I found myself, for the first time since I graduated from college, out of a job.

From there on I followed various branches of the financial world, ranging from investment counsel to membership of the stock exchange and finally ended as an adviser to a few individuals who had capital funds to look after. In the meantime, my major interest became very specific, which was to endeavor by some means of getting the educational world to actually, you might say, teach the subject of economics realistically and move it away from the support of various speculative activities that characterize our country.

I have had that interest, and you know how, as you generate a specific interest, you find yourself gravitating toward persons with similar interests, and ultimately I found myself in the center of the world of dissatisfaction with the directions that this country was headed. I found myself in contact with many individuals who on their own had done a vast amount of studying and research in areas, which were part of the problem.

E. G.: At what point in your career did you become connected with the Reece Committee?

N. D.: 1953.

E. G.: And what was that capacity?

N. D.: That was in the capacity of what they called Director of Research.

E. G.: Can you tell us what the Reece Committee was attempting to do?

N. D.: Yes, I can tell you. It was operating and carrying out instructions embodied in a resolution passed by the House of Representatives, which was to investigate the activities of foundations as to whether or not these activities could justifiably be labeled un-American without, I might say, defining what they meant by “un-American.” That was the resolution, and the committee had then the task of selecting a counsel, and the counsel in turn had the task of selecting a staff, and he had to have somebody who would direct the work of that staff, and that was what they meant by the Director of Research.

E. G.: What were some of the details, the specifics that you told the Committee at that time?

N. D.: Well, Mr. Griffin, in that report I specifically, number one, defined what, to us, was meant by the phrase, “un-American.” We defined that in our way as being a determination to effect changes in the country by unconstitutional means. We have plenty of constitutional procedures, assuming we wish to effect a change in the form of government and that sort of thing; and, therefore, any effort in that direction which did not avail itself of the procedures which were authorized by the Constitution could be justifiably be called un-American.

That was the start of educating them up to that particular point. The next thing was to educate them as to the effect on the country as a whole of the activities of large, endowed foundations over the then-past forty years.

E. G.: What was that effect?

N. D.: That effect was to orient our educational system away from support of the principles embodied in the Declaration of Independence and implemented in the Constitution, and the task now was the orientation of education away from these briefly stated principles and self-evident truths.

That’s what had been the effect of the wealth, which constituted the endowments of those foundations that had been in existence over the largest portion of this span of 50 years, and holding them responsible for this change. What we were able to bring forward, what we uncovered, was the determination of these large endowed foundations, through their trustees, to actually get control over the content of American education.

E. G.: There’s quite a bit of publicity given to your conversation with H. Rowan Gaither. Would you please tell us who he was and what was that conversation you had with him?

N. D.: Rowan Gaither was, at that time, president of the Ford Foundation. Mr. Gaither had sent for me when I found it convenient to be in New York, asked me to call upon him at his office, which I did. Upon arrival, after a few amenities, Mr. Gaither said: “Mr. Dodd, we’ve asked you to come up here today, because we thought that possibly, off the record, you would tell us why the Congress is interested in the activities of foundations such as ourselves?”

Before I could think of how I would reply to that statement, Mr. Gaither then went on voluntarily and said:

“Mr. Dodd, all of us who have a hand in the making of policies here have had experience either with the OSS during the war or the European Economic Administration after the war. We’ve had experience operating under directives, and these directives emanate and did emanate from the White House. Now, we still operate under just such directives. Would you like to know what the substance of these directives is?”

I said, “Mr. Gaither, I’d like very much to know,” whereupon he made this statement to me:

“Mr. Dodd, we are here operating in response to similar directives, the substance of which is that we shall use our grant-making power so to alter life in the United States that it can be comfortably merged with the Soviet Union.”

Well, parenthetically, Mr. Griffin, I nearly fell off the chair. I, of course, didn’t, but my response to Mr. Gaither then was:

“Well, Mr. Gaither, I can now answer your first question. You’ve forced the Congress of the United States to spend $150,000 to find out what you’ve just told me.”

I said: “Of course, legally, you’re entitled to make grants for this purpose, but I don’t think you’re entitled to withhold that information from the people of the country to whom you’re indebted for your tax exemption, so why don’t you tell the people of the country what you just told me?”

And his answer was, “We would not think of doing any such thing.” So then I said, “Well, Mr. Gaither, obviously you’ve forced the Congress to spend this money in order to find out what you’ve just told me.”

E. G.: Mr. Dodd, you have spoken before about some interesting things that were discovered by Katherine Casey at the Carnegie Endowment. Can you tell us that story, please?

N. D.: Yes, I’d be glad to, Mr. Griffin. This experience that you just referred to came about in response to a letter that I had written to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, asking certain questions and gathering certain information. On the arrival of that letter, Dr. Johnson, who was then president of the Carnegie Endowment, telephoned me and said, did I ever come up to New York. I said yes, I did more or less each weekend, and he said, “Well, when you’re next here, will you drop in and see us?” Which I did.

On arrival at the office of the endowment I found myself in the presence of Dr. Joseph Johnson, the president — who was the successor to Alger Hiss — two vice presidents, and their own counsel, a partner in the firm of Sullivan and Cromwell.

Dr. Johnson said, after again amenities, “Mr. Dodd, we have your letter. We can answer all those questions, but it would be a great deal of trouble, and we have a counter suggestion. Our counter suggestion is: if you can spare a member of your staff for two weeks and send that member up to New York, we will give to that member a room in the library and the minute books of this foundation since its inception, and we think that whatever you want to find out, or that Congress wants to find out, will be obvious from those minutes.”

Well, my first reaction was they’d lost their minds. I had a pretty good idea of what those minutes would contain, but I realized that Dr. Johnson had only been in office two years, and the other vice presidents were relatively young men, and counsel seemed to be also a young man, and I guessed that probably they’d never read the minutes themselves. So I said I had somebody and would accept their offer.

I went back to Washington and I selected a member of my staff who had been a practicing attorney in Washington. She was on my staff to see to it that I didn’t break any congressional procedures or rules, in addition to which she was unsympathetic to the purpose of the investigation. She was level-headed and a very reasonably brilliant, capable lady. Her attitude toward the investigation was: “What could possibly be wrong with foundations? They do so much good.”

Well, in the face of that sincere conviction of Katherine’s I went out of my way not to prejudice her in any way, but I did explain to her that she couldn’t possibly cover fifty years of written minutes in two weeks, so she would have to do what we call spot reading. I blocked out certain periods of time to concentrate on, and off she went to New York. She came back at the end of two weeks with the following on dictaphone tapes:

We are now at the year 1908, which was the year that the Carnegie Foundation began operations. In that year, the trustees, meeting for the first time, raised a specific question, which they discussed throughout the balance of the year in a very learned fashion. The question is: “Is there any means known more effective than war, assuming you wish to alter the life of an entire people?” And they conclude that no more effective means than war to that end is known to humanity.

So then, in 1909, they raised the second question and discussed it, namely: “How do we involve the United States in a war?”

Well, I doubt at that time if there was any subject more removed from the thinking of most of the people of this country than its involvement in a war. There were intermittent shows in the Balkans, but I doubt very much if many people even knew where the Balkans were.

Then, finally, they answered that question as follows: “We must control the State Department.” That very naturally raises the question of how do we do that? And they answer it by saying: “We must take over and control the diplomatic machinery of this country.” And, finally, they resolve to aim at that as an objective.

Then time passes, and we are eventually in a war, which would be World War I. At that time they record on their minutes a shocking report in which they dispatched to President Wilson a telegram, cautioning him to see that the war does not end too quickly.

Finally, of course, the war is over. At that time their interest shifts over to preventing what they call a reversion of life in the United States to what it was prior to 1914, when World War I broke out. At that point they came to the conclusion that, to prevent a reversion, “we must control education in the United States.”

They realize that that’s a pretty big task. It is too big for them alone, so they approach the Rockefeller Foundation with the suggestion that that portion of education, which could be considered domestic, be handled by the Rockefeller Foundation and that portion, which is international, should be handled by the Endowment. They then decide that the key to success of these two operations lay in the alteration of the teaching of American history.

So they approach four of the then most prominent teachers of American history in the country — people like Charles and Mary Byrd — and their suggestion to them is: will they alter the manner in which they present their subject? And they got turned down flat. So they then decide that it is necessary for them to do as they say, “build our own stable of historians.”

Then they approach the Guggenheim Foundation, which specializes in fellowships, and say: “When we find young men in the process of studying for doctorates in the field of American history and we feel that they are the right caliber, will you grant

them fellowships on our say-so?” And the answer is yes. So, under that condition, eventually they assemble twenty, and they take this twenty potential teachers of American history to London, and there they’re briefed on what is expected of them when, as, and if they secure appointments in keeping with the doctorates they will have earned. That group of twenty historians ultimately becomes the nucleus of the American Historical Association.

Toward the end of the 1920s, the Endowment grants to the American Historical Association $400,000 for a study of our history in a manner which points to what can this country look forward to in the future. That culminates in a seven-volume study, the last volume of which is, of course, in essence a summary of the contents of the other six. The essence of the last volume is: The future of this country belongs to collectivism administered with characteristic American efficiency.

That’s the story that ultimately grew out of and, of course, was what could have been presented by the members of this Congressional committee to the Congress as a whole for just exactly what it said. They never got to that point.

E. G.: This is the story that emerged from the minutes of the Carnegie Endowment?

N. D.: That’s right. It was official to that extent.

E. G.: Katherine Casey brought all of these back in the form of dictated notes from a verbatim reading of the minutes?

N. D.: On dictaphone belts.

E. G.: Are those in existence today?

N. D.: I don’t know. If they are, they’re somewhere in the Archives under the control of the Congress, House of Representatives.

E. G.: How many people actually heard those, or were they typed up, a transcript made of them?

N. D.: No.

E. G.: How many people actually heard those recordings?

N. D.: Oh, three maybe. Myself, my top assistant, and Katherine. I might tell you, this experience, as far as its impact on Katherine Casey was concerned, was she never was able to return to her law practice. If it hadn’t been for Carroll Reece’s ability to tuck her away into a job in the Federal Trade Commission, I don’t know what would have happened to Katherine. Ultimately, she lost her mind as a result of it. It was a terrible shock. It’s a very rough experience to encounter proof of these kinds.

E. G.: Mr. Dodd, can you summarize the opposition to the Committee, the Reece Committee, and particularly the efforts to sabotaging the Committee?

N. D.: Well, they began right at the start of the work of an operating staff, Mr. Griffin, and it began on the day in which the Committee met for the purpose of consenting to or confirming my appointment to the position of Director of Research. Thanks to the abstention of the minority members of the Committee, that is, the two Democratic members, from voting, technically I was unanimously appointed.

E. G.: Wasn’t the White House involved in opposition?

N. D.: Not at this particular point. Mr. Reece ordered counsel and myself to visit Wayne Hays. Wayne Hays was the ranking minority member of the Committee as a Democrat, so we came to him, and I had to go down to Mr. Hays’s office, which I did.

Mr. Hays greeted us with the flat statement directed primarily to me, which was that “I am opposed to this investigation. I regard it as nothing but an effort on the part of Carroll Reece to gain a little prominence, so I’ll do everything I can to see that it fails.”

Well, I have a strange personality in that a challenge of that nature interests me. Our counsel withdrew. He went over and sat on the couch in Mr. Reece’s office and pouted, but I sort of took up this statement of Hays as a challenge and set myself the goal of winning him over to our point of view. I started by noticing on his desk that there was a book, and the book was of the type that — there were many in these days — that would be complaining about the spread of Communism in Hungary, that type of book. This meant to me at least he has read a book, and so I brought up the subject of the spread of the influence of the Soviet world.

For two hours, I discussed this with Hays and finally ended up with his rising from his desk and saying: “Norm, if you will carry this investigation toward the goal as you have outlined to me, I’ll be your biggest supporter.” I said: “Mr. Hays, I can assure you that I will not double-cross you.”

Subsequently Mr. Hays sent word to me that he was in Bethesda Hospital with an attack of ulcers, but would I come and see him, which I did. He then said: “Norm, the only reason I’ve asked you to come out here is I just want to hear you say again you will not double-cross me.” I gave him that assurance, and that was the basis of our relationship.

Meantime, counsel took the attitude expressed in these words: “Norm, if you want to waste your time with this guy,” as he called him, “you go ahead and do it, but don’t ever ask me to say anything to him under any conditions on any subject.” So, in a sense, that created a context for me to operate in relation to Hays on my own.

As time passed, Hays offered friendship, which I hesitated to accept because of his vulgarity, and I didn’t want to get mixed up with him socially under any conditions.

Well, that was our relationship for about three months, and then, eventually, I had occasion to add to my staff a top-flight intelligence officer.

Both the Republican National Committee and the White House were resorted to, to stop me from continuing this investigation in the directions Carroll Reece had personally asked me to do, which was to utilize this investigation, Mr. Griffin, to uncover the fact that this country had been the victim of a conspiracy. That was Mr. Reece’s conviction.

I eventually agreed to carry it out. I explained to Mr. Reece that Hays’s own counsel wouldn’t go in that direction. He gave me permission to disregard their counsel, and I had then to set up an aspect of the investigation outside of our office, more or less secret.

The Republican National Committee got wind of what I was doing and they did everything they could to stop me. They appealed to counsel to stop me, and finally they resorted to the White House.

E. G.: Was their objection because of what you were doing or because of the fact that you were doing it outside of the official auspices of the Committee?

N. D.: No, their objection was, as they put it, my devotion to what they called anti-semitism. That was a cooked up idea. In other words, it wasn’t true at all, but anyway, that’s the way they expressed it.

E. G.: Why did they do that? How could they say that?

N. D.: Well, they could say it, Mr. Griffin, but they had to have something in the way of a rationalization of their decision to do everything they could to stop the completion of this investigation in the directions that it was moving, which would have been an exposure of this Carnegie Endowment story and the Ford Foundation and the Guggenheim and the Rockefeller Foundation, all working in harmony toward the control of education in the United States.

Well, to secure the help of the White House in the picture, they got the White House to cause the liaison personality between the White House and the Hill, a Major Person, to go up to Hays and try to get him to, as it were, actively oppose what the investigation was engaged in. Hays very kindly then would listen to this visit from Major Person, then he would call me and say, “Norm, come up to my office. I have a good deal to tell you.” I would go up. He would tell me, “I’ve just had a visit from Major Person, and he wants me to break up this investigation.” I then said, “Well, what did you do? What did you say to him?” He said, “I just told him to get the hell out.” He did that three times, and I got pretty proud of him in the sense that he was, as it were, backing me up. We finally embarked upon the hearing at Hays’s request, because he wanted to get them out of the way before he went abroad for the summer.

E. G.: Why were the hearings finally terminated? What happened to the Committee?

N. D.: What happened to the Committee or the hearings?

E. G.: The hearings.

N. D.: Oh, the hearings were terminated. Carroll Reece was up against such a furor with Hays through the activity of our own counsel. Hays became convinced that he was being double-crossed and he put on a show in a public hearing room, Mr. Griffin, that was an absolute disgrace. He called Carroll Reece publicly every name in the book, and Mr. Reece took this as proof that he couldn’t continue the hearings. He actually invited me to accompany him when he went down to Hays’s office and, in my presence with tears rolling down his face, Hays apologized to Carroll Reece for what he had done and his conduct, and apologized to me. I thought that would be enough and that Carroll would resume, but he never did.

E. G.: The charge of anti-semitism is intriguing. What was the basis of that charge? Was there a basis for it at all?

N. D.: The basis of what the Republican National Committee used was that the intelligence officer I’d taken on my staff when I oriented this investigation to the exposure and proof of a conspiracy was known to have a book, and the book was deemed to be anti-semitic. This was childish, but this was the second in command of the Republican National Committee, and he told me I’d have to dismiss this person from my staff.

E. G.: Who was that person?

N. D.: A Colonel Lee Lelane.

E. G.: And what was his book? Do you recall?

N. D.: The book they referred to was called Waters Flowing Eastward, which was a castigation of the Jewish influence in the world.

E. G.: What were some of the other charges made by Mr. Hays against Mr. Reece?

N. D.: Just that Mr. Reece was utilizing this investigation for his own prominence inside the House of Representatives. That was the only charge that Hays could think of.

E. G.: How would you describe the motivation of the people who created the foundations, the big foundations, in the very beginning? What was their motivation?

N. D.: Their motivation? Well, let’s take Mr. Carnegie as an example. He has publicly declared that his steadfast interest was to counteract the departure of the colonies from Great Britain. He was devoted to just putting the pieces back together again.

E. G.: Would that have required the collectivism that they were dedicated to?

N. D.: No, no, no. These policies, the foundations’ allegiance to these un-American concepts, are all traceable to the transfer of the funds into the hands of trustees, Mr. Griffin. It’s not the men who had a hand in the creation of the wealth that led to the endowment for what we would call public purposes.

E. G.: It’s a subversion of the original intent, then?

N. D.: Oh, yes, completely, and that’s how it got into the world traditionally of bankers and lawyers.

E. G.: How do you see that the purpose and direction of the major foundations has changed over the years to the present? What is it today?

N. D.: Oh, it’s a hundred percent behind meeting the cost of education such as it is presented through the schools and colleges of the United States on the subject of our history as proving our original ideas to be no longer practicable. The future belongs to collectivistic concepts, and there’s just no disagreement on that.

E. G.: Why do the foundations generously support Communist causes in the United

States?

N. D.: Well, because to them, Communism represents a means of developing what we call a monopoly, that is, an organization of, say, a large-scale industry into an administerable unit.

E. G.: Do they think that they will be the ones to benefit?

N. D.: They will be the beneficiaries of it, yes.