Did the A-Bomb Do Any Good?

February 21, 2017

Experts who never got within a thousand miles of the A-bomb have been answering this question since August 6, 1945. Here is an answer by two men directly involved in this epochal event

Where were you on the evening of August 6, 1945? Where were you when you heard the news from Hiroshima? It is a question every American old enough to hear the radio five years ago can answer. Where were you when the A-bomb dropped?

Recently, in a New York hotel room, two men met for the first time. To the question “Where were you on the morning of August 6th?” they had the same answer to make:

“Hiroshima! In the plane that dropped the bomb,” said Captain Robert A. Lewis, co-pilot of the historic B-29, the Enola Gay.

“Hiroshima! Breakfasting in the Rectory of our church,” said Father Hubert F. Schiffer, S.J., one of the few European victims of the bomb.

“For five years I have looked forward to meeting someone who saw it from the ground,” said Captain Lewis.

“I have wanted for five years to meet someone who was in the plane,” said Father Schiffer, a German Jesuit priest so badly injured by the explosion that he was able to leave his sickbed only after many months.

“And you are all right now?” the American captain asked.

“Oh, there are ten or fifteen radioactive glass splinters in my back they still don’t dare remove,” the young priest shrugged. “Don’t let that worry you.”

“Well,” said the pilot, “it doesn’t make me feel too good!”

The two men whose fates were so oddly linked are both in their early thirties. The priest is here studying labor relations at Fordham University, preparing for his return to mission work in Japan. Robert Lewis is personnel manager of Henry Heide, Inc., the New York candy firm. Both, then, are in the field of labor and its relations. Both of them have also strong convictions as to the need of peace in the world today, and both hope that the bomb itself will prove an instrument for bringing the dread of war so close to statesmen’s hearts that peace will be assured.

But the two survivors of Hiroshima share smaller and more intimate memories. That odd taste when the bomb went off, for instance. Neither of them could describe it; neither of them had found anyone else who shared that memory until now. And they had other

things to talk about…

Captain Lewis had prepared for the Hiroshima drop for years; since September of 1944, when he was secretly alerted for the “biggest project the Air Force will have to do” and was briefed at a hush-hush conference in Utah, on how to fly a bomb which the Army officials expected to end the war. The captain, even then, was an expert on the new B-29’s, which he had been test-piloting for many months, along with his commander, Colonel Paul Tibbets. Captain Lewis met with scientists who told him of the mystic symbols “U235” when only a handful of high government officials knew what they meant. He was trained to drop the bomb before the bomb was even made.

The preparations for the historic flight began in Wendover, Utah, at a flying field whose security precautions were almost neurotic in their exactitude. The town chosen had more Army intelligence men in residence than its peace-time citizens (only one-hundred men and women, bewildered to know what on earth was going on). No more than two atomic scientists were allowed out of Wendover on any of the experimental flights; certain scientists were judged so valuable they could never fly at all. When secret flights were made — to Los Alamos, N.M., certain Air Force officers wore false insignia and took a roundabout route to and from the towns they visited.

The 509 Composite Group was the hush-hush outfit’s final name; it was activated in December of 1944, trained in Cuba and in California. The ship herself came from the factory labelled 6292, but was given the more glamorous name of “Enola Gay” on her fateful mission.

So Captain Lewis had a pretty good idea of what he was going to be doing early in August of that year. “There were times,” he said, “when I wanted to go back to Piper Cubs. The scientists couldn’t tell us whether the bomb dropping would explode the plane or not. They ‘thought’ a safe distance would be three and a half miles away. Half of them — only half — expected the crew to survive!”

Where was President Truman on August 6th? He had just left Potsdam where he had been in conference with Marshal Stalin, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and later, Clement Atlee. The President wanted the Potsdam warning to Japan to be dramatized by the dropping of the bomb on August 2nd. Weather conditions caused four days’ delay. But every morning for those four days the crew of twelve men were alerted at dawn; every day until the 6th the weather closed down. On that morning, however, the skies were clear. The Operations officers reported good conditions ahead. The big flight was on.

There were three planes in the group that took off at 3 A.M. that day: the bomb ship, an instrument plane and a photographic plane which followed them several miles behind. The planes arranged to rendezvous at Iwo Jima, where a substitute plane was awaiting in case trouble should develop en route. Three weather ships had taken off an hour ahead to scout the three targets chosen as possibilities: Nagasaki, Kokura and Hiroshima. They reported — only 40 minutes before the Bombs away! — that the weather was best around Hiroshima. It was that slight matter of air currents and wind that thus determined the destiny of 400,000 people — including Father Schiffer.

The priest’s preparation for the event of August 6th had been a great deal less elaborate than the captain’s: he expected just another day. A German-born missionary, he had been studying in Tokyo since 1935 and had only recently been ordained. The living conditions in Tokyo at that time were difficult; nightly bombings made sleep a near impossibility and the young priest was sent, by his superiors, to the “quiet” town of Hiroshima for a rest. Here he was to work at the Jesuit Church of the Assumption of Our Lady.

On the morning of August 6th, Father Schiffer was quietly reading a Japanese newspaper at his breakfast table when the world went white about him.

(“It happened that way up above, too,” said Captain Lewis. “The glare when the bomb burst was so brilliant it made the sun seem pale.”)

The next thing the young priest knew he was lying down, recovering consciousness and very wet from his own blood. He could neither see nor hear. That frightened him, for in a bombing such as he had known before, there should have been much noise. Then he realized that he was deaf, and also that he was blind.

A few moments later, his senses returned and he gasped at what he saw. The walls, the windows, had been shattered into strange, irregular designs. The furnishings of the room had crumbled to dust. His own clothing had been swept away. His feet were bare. And he was in great pain.

A voice from above, the voice of his pastor, called to ask, “Father Schiffer, are you living?” (It was an odd question, he thought, even then: “He would ask if I were wounded unless he half expected me to be dead.”)

The pastor and two other priests, who had been upstairs, rushed down to join the gravely injured man. No one understood yet what had occurred. The rectory was earthquake proof, and its walls held. But the church next door had utterly disappeared. And as for the town —

“There is a doctor down that street,” the pastor said, and then his voice was still. There was no street. There was scarcely any city. There were only the horrible sights of ruination where men had lived their lives a few hours before.

Father Schiffer was obviously going to die; the pastor spoke accordingly.

“You will soon see the Blessed Mother in Heaven,” he told him. “Please tell her that we will rebuild her church on this spot as soon as we can.”

Father Schiffer moved a bit.

“Father,” he said to his superior, “I think I have a chance of life if I can crawl to the river and get some water. You may be able to give the message to the Blessed Mother before I do.”

So he set out for the river. A few hudred yards from the rectory he collapsed and lay there for twelve hours — until help could be brought from the Jesuit novitiate three miles outside the town. Then the wounded man was put into a hand cart and jounced over the rutted roads for an agonizing trip. At the novitiate there were no doctors, no nurses. It was the rector who looked at Father Schiffer’s back and said, “Why, man, you’re full of glass!” Over a hundred glass splinters had lodged in his back, and these the rector cut out, without anesthesia or proper surgical instruments.

That night more than a hundred Japanese patients were also brought to the novitiate, one by one. Some of them were kept as patients for a year or more, and fed out of the Jesuits’ own scanty wartime rations. Some of them had been picked up and added to the hand-cart caravan that brought the priest himself.

“Half a dozen times on that ride,” he said, “I begged the bearers, ‘Let me die here. It’s hopeless.’ They answered, ‘No. We have orders to get you back for a decent Christian funeral. If we leave you here you’ll be mixed up with all the other corpses.’ The other corpses were all around us where the road should have been.

“I know now,” the priest added gravely, “quite enough about what hell looks like to make my meditations on that subject with no prompting from the spiritual books.”

All these details of the effects on the earth below were a secret from the Americans in the B-29 until last month, when the meeting between the two men occurred. Captain Lewis has a vivid memory of all that happened in the air after the target was reached, after the Bombs away!

“Then,” the captain recalls, “we made a sharp turn to the right, as the scientists had warned us to. We were flying manually by instruments at above 30,000 feet. Forty-three seconds after we had dropped it, the A-bomb exploded, 1800 feet above the ground. My God! I felt a flash through my whole body… The scientists later said it was the ‘ozone effect.’ Then there were two distinct slaps at the ship about 20 seconds after the flash.

“The light was at my back, but even so it stunned me. It was fiercer than the sun on that bright and sunny day. Yet by that time we were maybe eight miles from the explosion. We had to get away fast to avoid the bomb effects ourselves. But later we could look back and see the mushroom.

“It looked as if the whole city were covered with boiling smoke. In three minutes it got up as high as 30,000 feet. We could see the flames below crawling up the mountains and covering the bridges and tributary rivers. It seemed impossible to comprehend.

“I thought, ‘My God! What have we done? If I live a hundred years, I’ll never be able to get this moment out of my mind.’ I guess I never will. We thought the Japanese might have surrendered by the time we got back to our base. It seemed like something out of Buck Rogers.

“Oh, I’d dropped bombs before … 10,000 pound bombs. But at 30,000 feet they make tiny little puffs of smoke when they explode. This was different. This was awful. Back at the base I slept for 20 hours. But later I didn’t sleep much. I’d lie awake thinking, ‘What if the bomb had gone off in the plane? What if we had lost a wing?’ Only half the scientists ever expected the crew to survive, remember. Yet none of us had even combat fatigue. It was a small sacrifice to end a war … on the winners’ part, anyway. Nobody connected with the bomb had to lose his life.

“But of course the loss of life in that city was terrible. We had picked it because it was an important Japanese headquarters … the Second Imperial Command was there.”

“Yes,” said Father Schiffer gently. “But that was just on paper. Hiroshima was a debarkation point for China, with about 100,000 Japanese soldiers stationed there. But there were no big military installations. It was a city of 400,000 civilians; of those at least 200,000 died.”

“Good heavens,” said Captain Lewis, “That many?”

“Yes,” replied the priest. “The Japanese official figures minimized the loss at the ridiculous figure of 80,000. We knew better.”

The pilot nodded. “I could see trolleys and little bridges going up … I don’t know how many.”

“Forty-two bridges were destroyed,” said Father Schiffer.

“Did you hear the bomb coming down?”

“I heard nothing,” Father Schiffer replied, “not the plane, nor any impact. That scared me most when I recovered consciousness. I lay there waiting for the next bombs to drop, the way they always had in raids before. The silence was the most appalling thing of all: no screams, no air raid signals, no fire engines rushing past.”

“Did you have any sensation of heat?”

“I don’t remember… Anyway, it was a very hot day. But when I regained my sight, I looked about and tried to count the fires… There are always fires in those wooden cities of Japan. I counted sixteen in the first ten minutes. By that time it had become very cloudy, but I didn’t look up or see the mushroom.

“There was too much to hold my eyes to the earth: blood in the streets and flattened houses with no living men about. It didn’t look nice.”

“I went back to Japan after the war,” said Captain Lewis, “And the Japs in Tokyo had the damnedest reaction to the bomb you ever heard. They seemed grateful for it. They called it ‘God’s Wind’ and said it had saved many lives by bringing an end to the war.”

Father Schiffer nodded.

“I know,” he said, “We thought we knew the Japanese psychology well after fifteen years, but their reaction at Hiroshima amazed even us. The survivors there felt their city had been given a unique honor … that of suffering in order to bring peace to the world. They look upon their 200,000 dead as willing victims, as heroes sacrificed for world-wide peace.”

“Were the survivors themselves crippled by radioactivity?”

“No,” said Father Schiffer, “not unless they had had specific injuries. Many Hiroshima citizens were bald … some for years … but now their hair has been restored. There was no sterility-effect, according to the doctors on the spot, and no increase in the birth of abnormal babies.

“The survivors of Hiroshima are scarcely worse off physically today than before the bomb. Spiritually, they are far, far better.”

“And what do you mean by that, Father?” asked Captain Lewis.

“Well,” said the priest, “it is a happy ending. I’ll tell you…

“The Japanese Diet has allotted funds to build a University of Hiroshima as a symbol of peace! That in itself is startling. But much more than that is going on…

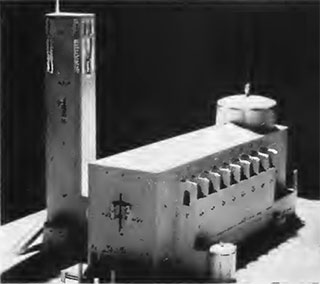

“Our missionaries there were recently approached by a committee of leading citizens … Buddhists, for the most part. Before the war this city was predominantly Buddhist. Well, these men approached our rector and asked if we would build a ‘palace of prayer’ for peace right where the A-bomb fell. He was also asked if he would supply lecturers to speak in Buddhist monasteries nearby. Conversions to Christianity are soaring and the ‘palace of prayer’ is to be built.

The Tokyo newspaper Asahi recently conducted a contest among architects for the best plans for this memorial shrine, and some of Japan’s foremost architects competed for the honor of designing the structure. Construction should be under way by the time this article is in print.

Flags of all the countries engaged in World War II will be placed on the altar and prayers will be offered up twenty-four hours a day not only for the future peace of the world but for all the dead and wounded of the war. Names of Buddhist, Catholic, Protestant and Jewish veterans are already being inscribed in a Golden Book of Prayer which the Franciscan Adoration Monastery of Cleveland is preparing for the shrine, scheduled for completion on August 15, 1952 to coincide with the Feast of the Assumption.

Already Father Schiffer has built an orphanage at Hiroshima where 65 children are being cared for, and this is to be expanded to a general hospital in time.

And so the effects of the A-bomb on Hiroshima have included things that never crossed the minds of the General Staff in Washington, nor of the scientists who discovered how to release the devil that uranium contains, nor, certainly, of the B-29 crew. For peace and love and prayer will mark the spot, forever, where the A-bomb fell.

“Will you fly back to Hiroshima when we open our shrine, captain?” asked the priest gently. “Will you try to borrow a B-29 and land it at the spot you saw go up in smoke before?”

“Will I?” said Captain Lewis. “Will I? If I can do that, and maybe bring a plane-load of candy from America for those kids, I’ll never have nightmares again over the damage that we had to do that day. I’ll agree with you, the story of Hiroshima had a happy ending.”

Illustration by Matt Greene

Digital discoveries

- Migliori Casino Online

- Casino Non AAMS

- Siti Casino

- Sites De Paris Sportifs Belgique

- Tous Les Sites De Paris Sportifs Belgique

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne Belgique

- Casino En Ligne Belgique Bonus

- I Migliori Casino Online

- Non Aams Casino

- Scommesse Italia App

- Migliori Casino Online Esteri

- Paris Sportif Crypto Sans Kyc

- Site De Paris Sportif

- Sweet Bonanza Avis

- Paris Sportif Ufc

- オンラインカジノ 出金早い

- Casino Live En Ligne Français

- Site De Paris Sportifs

- Meilleurs Nouveaux Casinos En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne Français

- Casino En Ligne

- Casino Retrait Instantané

- Casino En Ligne Fiable

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne 2026

- Casino En Ligne Retrait Immédiat

- Casino Français En Ligne

- Casino Italia Non Aams

- Casino Con Free Spin Senza Deposito

- Siti Di Scommesse Non Aams

- Migliore Casino Non Aams

- Casino Online Non Aams 2026

- 토토사이트 모음

- Top 10 Trang Cá độ Bóng đá

- Casino En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne France

- Casino En Ligne Argent Réel

- Casino En Ligne Retrait Immédiat 2026

- Nouveau Casino En Ligne 2026