Chains in the Baltics

July 14, 2018

Only a handful of men in the entire world had access to the material that passed through Albert Konrad Herling’s hands. He was Director of Research for the United Nations’ Commission of Inquiry into Forced Labor. Albert Herling had interviewed hundreds of former inmates of Soviet labor camps and had a thick pile of Soviet documents, some of them represented by photostats in his book, The Soviet Slave Empire (1951).

When reading this chapter, bear in mind that this is the state of affairs that the Kremlin today is dreaming to restore.

1.

On November 15, 1917, V. Ulyanov-Lenin, Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars, and Josif Djugashvili-Stalin, People’s Commissar for National Affairs, enunciated a policy of self-determination in these ringing terms:

This policy [i.e., the former policy] must now be superseded by an open, honest policy leading to complete reciprocal confidence among Russia’s peoples. Only on such a foundation is it possible to achieve an honest and durable union of all the Russian peoples and to weld the workers and peasants into one revolutionary force, capable of resisting all the plots of the imperialistic and annexionist bourgeoisie.

Proceeding from these viewpoints, the first congress of Soviets in June proclaimed the right of the Russian peoples to free self-determination. The second congress of Soviets in October confirms this inalienable right of the Russian peoples still more securely. Executing this determination of the congress, the Council of People’s Commissars has decided to adopt the following principles in its dealings with nationalities:

- Freedom and sovereignty to the peoples of Russia;

- The right for Russia’s peoples of free self-determination even unto separation and establishment of independent states;

- Abolition of all and every kind of national and nationally religious privileges and restrictions;

- Free development for national minorities and ethnographical groups inhabiting Russian territory.

The concrete regulations required by the above are to be drawn up without delay as soon as a commission for national affairs is formed.

Then again on February 2, 1920, at Tartu a treaty between Russia and Estonia was signed. This treaty declared (Article 2) that:

On the basis of the right of all peoples freely to decide their own destinies, and even to separate themselves completely from the State of which they form part, a right proclaimed by the Federal Socialist Republic of Soviet Russia, Russia unreservedly recognizes the independence and autonomy of the State of Estonia, and renounces voluntarily and forever all rights of sovereignty formerly held by Russia over the Estonian people and territory by virtue of such former legal situation, and by virtue of international treaties, which, in respect of such rights, shall henceforth lose their force.

Substantially the same phraseology was used in the treaties with Latvia and Lithuania. Yet nineteen years later, in conspiracy with Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union invaded these independent states. These Baltic states became Soviet states in 1940; yet, in the confusions of 1941, the NKVD and General Staff left behind a map dated 1939 describing these states as Soviet Republics. The annexation by conquest of these states has not been recognized by the United States, and in effect, the deportation of the Baltic peoples to the slave-labor camps of the Soviet Union represents the second large group of non-Soviet peoples subjected to the slave-labor system which the Soviet citizens had known too well for a long time.

Testifying before the Commission of Inquiry into Forced Labor on February 24, 1949, the former Estonian Minister for Foreign Affairs, Kaarel R. Pusta, Sr., declared:

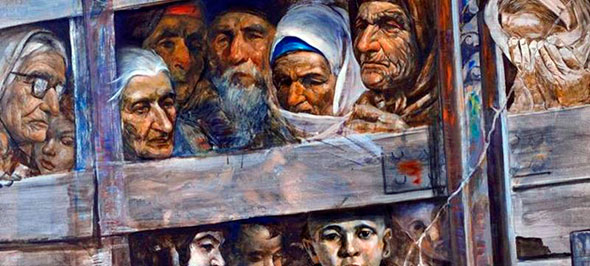

On November 22, 1947, an appeal had been presented to the President of the General Assembly of the United Nations by the diplomatic representatives of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, accredited in the United States, which exposed “a planned, systematic, and cruel genocide” in the Soviet-occupied Baltic States. According to this document, during one single week (June 14–21, 1941) 34,260 Lithuanians were deported in freight cars and in such inhuman conditions that thousands died in the trains and in transient prisons before reaching their destination. While husbands were separated from their wives and children from their mothers, the destination for the surviving men was slave-labor camps in Northern Siberia, in the Altai mountains, and in Kazakhstan. The women were sent to collective farms or to the fishing industry at the mouth of the river Lena. Of the children almost nothing is known.

At the same time 15,000 Latvians were arrested and deported, while in two and a half months (April–June, 1941) 60,000 Estonians disappeared. The ill-famed deportation center of Vorkuta, amidst the polar tundra of Northern Russia, held 100,000 Lithuanians, 60,000 Latvians, and 50,000 Estonians, in October 1946. Although on the average 25–30 per cent of the inmates are reported dying every year, the loss is filled by regular “deliveries” of 1,500 to 3,000 persons a month from each of the three Baltic countries.…

According to a statement of the Soviet broadcasting station in Tallinn, of May 14, 1946, the population of Estonia, which totaled 1,134,000 inhabitants on January 1, 1939, had decreased by a quarter “in consequence of the war events.” Now, according to Colonel Bulineh, a Soviet repatriation officer in Germany, Estonia has a total of 1,500,000 inhabitants in December 1947. The explanation of this sudden increase of population is that multitudes of Russians have been brought to Estonia and the other Baltic countries, while the native population has been shifted to remote places in Arctic Russia, Siberia, Kamtchatka, Sakhalin, and even to the Kurile Islands, formerly in the possession of Japan. For instance, near Habarovsk, about two million acres have been reserved in the wilderness for the resettled Estonian farmers.…

Witnesses who escaped to Sweden have stated that there are also many slave-labor camps in the Baltic States. A large concentration camp is situated at Kohtla-Jarve, Estonia, where Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians, and Finns from Carelia are working in the oil-shale mines. Other larger camps are at Lavassaare and Vasalemma (Estonia), to provide labor for the peat industry and the limestone quarries. The ruins in the war-razed towns were cleared away mostly by slave labor.

The establishment of new armament plants, and the realization of projects required by the Soviet Five Year Plans, require great masses of cheap man power. Mass arrests and deportations therefore never cease in the Soviet Union. In order not to waste labor the death penalty was allegedly abolished in 1947, and replaced by penal servitude, either for life or a great number of years. Yet not over five years of this servitude can be sustained by an average healthy person. The slave-labor camps’ population consists mainly of workers and peasants, but there are also members of national governments, diplomats, writers, and clergymen, all those who had no chance to escape to Sweden or the DP camps in Western Europe.

It also seems clear that these Soviet measures intend an indirect extermination of Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians—a crime which is termed genocide. A large part of the present populations is already composed of alien intruders, since the Russians have been settled in the Baltic countries as peasants and workers. Even the names of the expelled Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians have been given to them. [Italics mine.—A.K.H.]

From Stockholm, Sweden, the former President of the Republic of Estonia, Dr. A. Rei, wrote the Commission of Inquiry into Forced Labor that:

In the summer of 1941 the German army drove the Soviet occupational army out of Estonia and occupied the country in its turn. The German occupation, which lasted until the autumn of 1944, did not differ essentially from the Soviet one, and the Estonian people was further decimated by Nazi murders, arrests, and deportations.1

By October 1944 Estonia was reoccupied by the Soviets, who again treated the Estonians with the same brutality as under their first occupation. It has not been possible to ascertain with accuracy how many Estonians have been arrested, murdered, or deported to Russia during the second Soviet occupation. However, from the testimony of people who have lately escaped from Estonia, it must be concluded that from 1944 until this writing (February, 1949) the number of the arrested and deported is much larger than during the first occupation. During both occupations Estonia has lost altogether over 10 per cent of her entire population.

All the men who had been forcibly and unlawfully conscripted by the Germans and fallen into Russian hands were deported to forced labor in Russia as early as 1944 and 1945, mainly to the neighborhood of Leningrad and Northern Russia.

Before Christmas in 1945, and in February 1946, two great mass deportations took place, similar to the one on June 14–16 under the first occupation in 1941.

Individual arrests are undertaken every night. At Tallinn, which had only one prison while Estonia was independent, there are now four prisons. The moment one of them is full, the inmates are sent to slave-labor camps in Russia in the notorious cattle wagons. The people live in constant terror, for nobody knows when his or her turn to be arrested or deported may come.…

The entire population of some Estonian islands, which are now used as naval bases, have been deported either to the Caspian Sea or the shores of the Pacific Ocean in the Far East.

However, not only the Estonians in Estonia are being deported to Russia, but also Estonians found by the Russians in Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Eastern Germany as displaced persons, where the Germans had forced them to work in war industries and even drafted some into their armed forces. The latest of these deportations took place in the spring of 1948, when with the help of the German police the Russians rounded up the few Baltic nationals remaining in Eastern Germany and sent them to Russia.…

It is not stretching the facts to say that the program of labor-reserve schools for youths between the ages of 14 and 17 is a thinly veiled system of compulsory labor. A decree of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR dated October 2, 1940, ordains the foundation of schools for so-called labor reserves (factory, railway, nautical and industrial schools) and the drafting of children and minors into these schools.

The decree [writes Mr. Rei] provides for the forcible enrollment of minors between the ages of 14 and 17 in the labor-reserve schools, roughly at a ratio of two minors per every 100 inhabitants. The local executive committee make their selection among the boys of the above age, and neither the children themselves nor their parents have any say in the matter.… Thousands of Estonian boys have been deported to Russia in this manner, while Russian boys have been brought to Estonia to attend the labor-reserve “schools” and, later, to work in Estonian industries. On May 28, 1948, the Tallinn radio announced that until the completion of the present Five Year Plan (i.e., until 1950) it is proposed to put 40,000 Estonian boys through these schools. Actually this means that 40,000 children have been condemned to compulsory labor.

2.

Returned German prisoners of war, especially those repatriated from the Baltic States, are an excellent source of information. The substance of what these returned prisoners have told reveals the story pretty much this way.

In July, 1948, the Soviets carried through a large-scale deportation in the town of Vilnius and its environs (Vilnius is in Lithuania). The POWs got a day’s holiday, owing to the fact that the lorries which usually take them to their place of work were requisitioned by the MVD for the task of deportation. Even regular troops participated in the action.

Units of the Soviet Army and the MVD police surrounded whole villages or blocks of houses in the towns. Patrols penetrated into the villages and houses and seized the deportees, who were driven to the railway stations, where cattle trains with barred windows awaited them. In the villages all people who had held any public office in independent Lithuania, and all those considered “politically unreliable,” as well as farmers who had refused to join kolkhozes, still owned two horses, or had a well-cared-for farm, were branded as “kulaks” and carried off. They got a quarter of an hour to pack their luggage. Even their families had to follow them into exile.

The cattle trains carrying off the unfortunate deportees were sealed almost hermetically; had heavily barred windows; and lacked even the most primitive conveniences for the transport of people. Moreover, up to 80 persons were squeezed into cars which might hold 40 persons at the most. Lithuanians estimate that between 70,000 and 80,000 people were deported in the summer of 1948.

Latvia too was the scene of a deportation drive during this same period. German POWs returning from the USSR declared that they met, in Central Russia, between Kuibyshev and Smolensk, 25 goods trains with deportees from Latvia. The men had been separated from the women and children. The majority of the deportees had been farmers; and the MVD had given them 30 minutes to pack their belongings before taking them away from home. Every person had been allowed 30 kilograms of luggage. The reason for deportation, as far as the deportees had been able to elicit, had been their general anti-Soviet attitude and refusal to join kolkhozes voluntarily.

Several sources maintain that three Soviet tank divisions had been commandeered to Latvia to help carry through the deportation and quell possible revolts. It was said that this deportation was greater than the one in 1941. In addition to the above trains, seven goods trains with deportees were seen on the line between Kalinin and Brest-Litovsk with civilian prisoners from Latgallia. The majority were women and children, with a small number of old men. According to the women, the younger men had been deported earlier.

A released German N.C.O., who had come from Siberia, met Latvian deportees in a settlement on the River Tura in February of 1949. They were for the most part women, old men about 60 to 70 years of age, and a very small number of children. The forced laborers worked at a sawmill, carrying planks and boards the whole day. At a temperature of –40° F they wore wooden shoes. The only food they had in the first weeks of their stay was the food they themselves had been able to take with them.

Letters smuggled out of Latvia in April and May of 1949 give the information that the deportation went on during the whole of April. On some of the railways there had been no civilian traffic because of them. The districts adjoining the seashore were most savagely harried. From the port of Ventspils alone (population about 15,000) 60 cattle wagons with people had gone off to Siberia. A rumor in Latvia had it that this time the deportees had not been sentenced to penal servitude for any fixed number of years but were permanently resettled in the more desert regions of Soviet Asia.

On October 28, 1949, the Commission of Inquiry into Forced Labor received a report to the effect that Latvian industry was run almost exclusively by prisoner-of-war and convict labor. By the time the report was received, the situation had changed, but there are still plants, such as the Factory of Electrotechnical Machinery in Riga, to which penal camps are attached, whose inmates supply the plants in question with labor. There is every reason to believe that POWs and convicts are included in the total of 118,000 workers announced by the Soviet authorities.

This figure was released by the authorities to show a 20 per cent increase in the number of workers over 1938. As a matter of fact, this increase was obtained in spite of the severe war losses in the area, the escape of many people, and especially the deportations undertaken by the regime. The precarious labor-supply situation in the towns at the beginning of the second Soviet occupation (many workers had drifted to the country) resulted in the drafting of “free labor,” the use of prisoners of war and convict labor, and the importation of labor from Russia. Without these aids Latvian industry could not get going.

Aside from the very general provisions of the Soviet Criminal Code now applicable, of course, in the Baltics, the labor force needed by the MVD is secured in other ways as well. The “Operative Register” (1939–41) of the NKVD listed 29 classifications of persons to be “registered for later arrest or deportation to Russia.” The “Operative Register” is a secret manual, used particularly in connection with the arrests to be made in the “new Soviet Republics” of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia. Following are the classifications of persons to be deported:

- Trotzkyites.

- Anarchists.

- Terrorists.

- Social Revolutionaries.

- Prominent members of the Estonian (or Lithuanian, or Latvian) anti-Communist Parties, viz., Social Democrats, Liberals, Small Farmers, Agrarians, etc.

- Counter-revolutionary Fascist elements.

- Active members of anti-Soviet organizations.

- Active members of Jewish counter-revolutionary organizations, viz., the “Bund,” Zionist organizations, etc.

- Active members of White Russian emigrant organizations

- Various anti-Soviet elements, such as defeatists, spreaders of rumors, etc.

- Participants in anti-Soviet manifestations, viz., strikers under the Soviet regime, opponents of the kolkhoz system, etc.

- Mystics, such as Free Masons and theosophers.

- Persons who had occupied prominent positions in the civil or communal service of independent Estonia.

- Commissioned and noncommissioned officers in the standing army.

- Active and prominent members of the Home Guard.

- Policemen.

- Frontier guards with anti-Soviet leanings.

- Prison personnel.

- Public prosecutors, magistrates, and lawyers who had fought the Revolution; all the public prosecutors in political cases.

- Industrialists, wholesale merchants, owners of large houses, great landowners, shipowners, owners of hotels and restaurants.

- Persons of aristocratic descent.

- Persons who have been in the diplomatic service.

- Permanent representatives of foreign commercial firms.

- Relatives of persons who have escaped abroad.

- Persons whose relatives have engaged in anti-Soviet propaganda abroad.

- Spies.

- Germans.

- Close relatives of persons convicted under the Soviet regime.

- Criminal elements, viz., prostitutes, speculators, hiders of arms, owners of brothels, etc.

Classifications such as these assure an adequate supply of labor for the vast industrial enterprises of the MVD.

3.

Inasmuch as collectivization of agriculture in the Soviet Union contributed so much to the establishment of the forced-labor camps on their present huge scale, it is both interesting and important to watch the process in the latest areas incorporated into the Soviet Union, namely, the Baltic States.

The task of convincing the individualistic farmers in the Baltic States that they must join the kolkhoz system is not easy. One of the first steps in the convincing process is to deprive the farmer of his land by imposing upon him heavy quotas of produce to be delivered to the State; also equipment and livestock so that the newly founded kolkhozes in the Baltic Republics may be equipped. The authorities also exact of the farmers heavy statute labor, and failure to perform the imposed work involves severe penalties. Statute labor is compulsory labor similar to the work which serfs had to perform for the benefit of their feudal lords.

There are two types of statute labor—that performed by individual persons or farms, called individual statute labor; and collective statute labor, performed jointly by several persons or farms. The performers of individual statute labor receive, as a rule, a minor and totally inadequate compensation (in forest work and some types of road improvement), or no compensation at all (miscellaneous or incidental work). No remuneration at all is paid for collective statute work.

In the rural districts there are a number of compulsory statute labor types. Their fulfillment is checked by different officials and Party functionaries. Every farmer, man or woman, who manages a farm must perform the following statute labor:

- cut a specified amount of lumber;

- cart a specified amount of lumber to railway stations, rivers or lakes, or sawmills;

- repair a section of specified length of the rural roads and transport the necessary material;

- perform public carting service with the aid of horse-drawn vehicles.

In addition to the statute labor outlined, the incidental labor the farmers are required to do includes:

- clearing highways of snow in the winter;

- participation in the construction of fortifications;

- various transportation services, such as carting building material for public edifices, or for highways maintained by the government.

Then there is the collective statute labor to be performed. Government agencies impose on each administrative district a specified amount of statute labor; the district executive committee divides this amount among the individual communes and villages in its area; the executive committees of the villages and communes and the local Party functionaries divide the amount of statute labor imposed on the communes and villages among individual farms “according to plan and diagram.” Only officials of the executive committees, Party functionaries, and a few other minor groups (for example, invalid veterans and the like) are exempted from statute labor.

The volume of statute labor may occasionally differ in individual districts and communes, depending on the object of the statute labor, such as the size of forests, and the density of the network of roads. But farmers are not exempted from statute labor if, for example, neither forests nor the roads to be fixed are in their communes. In such cases they must perform their quota of labor outside their commune, or, at times, even outside their district. In the winter of 1949 hundreds of farmers had to travel 80 to 100 kilometers (irrespective of road conditions) in order to perform compulsory lumber cutting and carting work outside their communes. To visualize the difficulties besetting the farmers in such cases, it must be added that they must take with them food and fodder for several weeks, and material for the repair of tools and vehicles. Practically nothing beyond lavish propaganda literature is available on the sites of work.

On an average, the forest statute labor in the winter of 1949 was as follows:

- cutting: for a woman 16 cubic meters of lumber, for a man 30 cubic meters;

- carting: for each horse a quantity of 60 cubic meters to be transported to an indicated place.

Women farmers whose husbands are dead, missing since the war, or have been exiled to Russia are not exempted from this statute labor.

Even in cases where the statute labor is well organized, a considerable number of farmers must make strenuous efforts, occasionally working at night, in order to perform the imposed labor without greatly exceeding the time limit set. Organization, however, is often far from satisfactory. Here is what the newspaper Cina (published in Riga) of February 15, 1948, reports with respect to the Tukums district:

It has frequently occurred that cutters come to the forest and find that there is nobody who can assign them the sectors to be cut. Carters who have loaded their carriages must often wait for hours until they are given documents permitting unloading. The checking of lumber is very slow, etc.

Individual road repair work means that a farmer must repair a road section of between 200 and 300 meters. He must transport gravel and other necessary material; even cut the track and dig or improve the ditches along the road. This is one of the heaviest types of statute labor, especially for farms which lack horses and man power, as confirmed by the press. A correspondent of the official paper Cina reported (February 15, 1948) the following incident in the Tukums district:

The road maintenance tasks have in numerous cases been distributed in an improper manner. Working farmer Pavare, an old woman, had thus to repair 300 meters of road which is in a disgraceful state. It is plain that she is not able to repair this road section. The village council instructed the road commission to check the road distribution plan and to see to it that badly damaged roads which cannot be repaired by individual efforts be improved collectively.

Each farm with at least one horse must also provide, for the so-called general services (such as transportation of officials and other carting), a horse-drawn vehicle with a driver for a specified number of days each year. The number of days varies greatly in individual communes.

The farmer must also spend much time in performing nonperiodical statute labor, especially in areas where fortifications and other constructions are being built. This type of statute labor must not infrequently be performed during the harvesting and sowing seasons, and without any compensation.

In addition to the individual statute labor already described, the farmers must perform collective statute labor several weeks a year for work which cannot be done individually. The main types of this labor are road repairs and filled drainage.

A resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers of the Latvian Soviet Republic and the Central Committee of the Latvian Communist Party set aside a “road-work month” every year from May 25 to June 25. During this period all the major highways and bridges in Latvia are repaired. Highway boards and district and communal executive committees must see to it that all district, commune, and individual farmers perform their tasks in road repair in good time and in the proper manner.

Compulsory drainage work is usually organized from June 5 to July 5. The Riga-Madon radio station reported on June 9, 1948, that 12,886 persons participated daily in this action in the month of June.

Failure to perform the imposed statute work makes a person liable to severe punishment. A case was reported in Cina February 10, 1948, of one “Alvine Puraine, owner of the Abaci farm in the Brukna commune of the Bauska district, who had to cut 70 cubic meters of firewood last year and to cart this quantity before March 1948. She has failed to do so. The court sentenced this saboteur of forest work to two years’ imprisonment and the confiscation of all personal property.” The newspaper omitted to say that the convict faced deportation to Siberia, as no criminal with a sentence of two years or more is allowed to serve it in his or her homeland.

One wonders how and when these unfortunate people are able to perform all the compulsory work imposed upon them, since they must also attend to their own farms in order to earn a living and to complete the high compulsory deliveries of farm produce. This of course is possible only if they work 18 to 20 hours a day without any holidays. Tired and worn-out farmers cutting wood at night are no unusual sight in the Baltic countries today.

One hundred and fifty years ago the peasants of the Baltic States had to perform statute labor. The Baltic States at that time were under the domination of feudal lords in a feudal society. The difference between now and then is only in the severity of the punishments imposed: whereas eviction from his farm was the severest punishment which could be given a farmer for failure to fulfill his obligations under the statute labor of feudal times, now the punishment includes the confiscation of his entire personal property and deportation to Siberia.

Perhaps the best picture of the collectivization process is from the speeches and newspaper items in the Estonian press.

On December 25, 1949, for example, the chairmen of the Estonian kolkhozes were convened in Tallinn. One of the speakers was N. Karotamm, the first secretary of the Estonian Communist Party. In his speech he declared:

Our kolkhozniks should know what the state expects of them, and that is that every kolkhoznik should give his best towards the flourishing and prosperity of the state. This prosperity is sabotaged by the kulaks and their slavish hangers-on. We must cast out all this refuse from our midst, for in the Socialist society there is no place for sluggards and insubordinates.…

Twenty per cent of our peasants have not joined kolkhozes yet, but this state of things must now be ended. The agitators [i.e., the members of the agitation and propaganda sections of the Communist Party] are bound to see to it that these adherents of capitalistic comforts join the kolkhozes voluntarily without delay, for an individual farm in the middle of kolkhoz fields is like an island in the middle of the ocean which must be skirted.

We cannot tolerate this, and the agitators must make it plain to these opponents of collectivization that they must either join a kolkhoz voluntarily or pack their bags and WE WILL FIND A PLACE FOR THEM ELSEWHERE. At the same time the agitators should not be in too great a hurry: THESE PEOPLE SHOULD BE GIVEN TWENTY-FOUR HOURS FOR THOUGHT.

Karotamm then announced that for 1950 the compulsory deliveries must be discharged by July 20. He said:

Next year will see the completion of four years of the Five Year Plan, and by that time we must keep our promise to Stalin—fulfill the Five Year Plan in four years. In the towns things are not so bad—there we shall carry out the plan somehow; but in the country there are many shortcomings, and last year the peasants delivered only 18 per cent over and above the quota. In order to fulfill the plan we must give 46 per cent over and above the quota this year. And therefore we must make the greatest efforts next year in order not to be “a black sheep” in a flock of white ones. We must sow more, we must reap more, we must work with greater fervour, we must work by night if the day proves too short.…

All of you know how the kulak exploited his poor hired men; and now, when these hired men are free from kulak slavery, they do not want to work, although they know that all they accomplish profits them alone and their future prosperity. You say we are at the end of our forces. That is no excuse; we must find new forces. The Soviet regime knows no such words as “I am at the end of my strength,” “I cannot,” “I do not want to.”

The will to work of all the workers has increased; only in the countryside there is grumbling and malingering. This must end; laziness must stop; and the handles of the plow be grasped firmly. Thereby you will pay to the party and the government that great debt which you owe them for your liberation from capitalist slavery.

The Czarist regime exploited the workers, but that was only a tender caress as compared to the exploitation by Estonian “grey barons” [kulaks] and capitalists. For whom did you work then? For those who sucked your blood. Now you work for the state. And who is the state? You yourselves, dear comrades. You have said here that you are punished unjustly when failing to deliver your quotas “because there is not enough produce to deliver.” This is an arrant lie; nobody punishes you unjustly, for, as I have mentioned before, Soviet punishments are severe but just.… In our country there are no longer any bourgeois courts or any bloodthirsty bourgeois police, but Soviet courts and a Soviet militia.

You must understand that we must and want to keep our promises to Stalin, and that every attempt to interfere by the enemies of collectivization will be crushed in embryo.

As harsh as the speech was, a harshness which is plainly obvious, it should be pointed out that one major project is plainly absurd, because impossible of accomplishment. Karotamm demanded that all the compulsory quotas of agricultural produce must be delivered by July 20, 1950. The only possible crop which could be delivered by that time is hay; all other crops ripen considerably later in Estonia. For example, rye is not harvested before the end of July; wheat, oats, and barley in August. The only possible reason for this demand made by the Communist authorities may be in the fact that in the Ukraine and the southern regions of the Russian SFSR the crops are indeed ripe by that time, and the All-Union plan is compiled with these regions in mind. If Karotamm’s order were carried out, the Soviets would receive only green corn from Estonia, which would rot in a few weeks, and at best could be used only as fodder.

In any case, failure to deliver the crops may certainly be declared sabotage and counter-revolutionary subversion, thus providing for the roundup of those who might still be holdouts from the kolkhoz system.

But there is still another design in this. Reference has been made to the mass expulsions of peoples from Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. An analysis of the areas from which these people have been removed indicates that there has been a systematic removal of peoples from the areas bordering on the old boundaries of the Soviet Union from the Gulf of Finland to the shores of the Black Sea, and the resettlement of these areas with Soviet citizens from the eastern reaches of the Soviet Union. These newly settled people are unable to carry on any intercourse with the inhabitants of the nearby regions for want of similar language and culture. This, then, constitutes another compelling reason for the forcible removal of peoples from their homeland—the creation of a “sanitary” strip to keep the infection of unorthodox ideas even more completely away from the Soviet Union proper.

It may be appropriate to present here the orders issued by the NKVD (or MVD) regarding the manner of conducting the deportation of “Anti-Soviet Elements from Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia.” The following order from the files of the NKVD is presented almost in its entirety.

STRICTLY SECRET

INSTRUCTIONS

Regarding the Manner of Conducting the Deportation of the Anti-Soviet Elements from Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia

1. General Situation

The deportation of anti-Soviet elements from the Baltic States is a task of great political importance. Its successful execution depends upon the extent to which the county operative triumvirates and operative headquarters are capable of carefully working out a plan for executing the operations and foreseeing in advance all indispensable factors. Moreover, the basic premise is that the operations should be conducted without noise and panic, so as not to permit any demonstrations and other excesses not only by the deportees, but also by a certain part of the surrounding population inimically inclined toward the Soviet administration.

Instructions regarding the manner of conducting the operations are described below. They should be adhered to, but in individual cases the collaborators conducting the operations may and should, depending upon the peculiarity of the concrete circumstances of the operations and in order to evaluate correctly the situation, make different decisions for the same purpose, viz., to execute the task given them without noise and panic.

2. Manner of Issuing Instructions

The instructing of operative groups should be done by the county triumvirates within as short a time as possible on the day before the beginning of the operations, taking into consideration the time necessary for traveling to the place of operation.

The county triumvirates previously prepare necessary transportation for transferring the operative groups to the villages in the locale of operations.

In regard to the question of allotting the necessary number of automobiles and wagons for transportation, the county triumvirates will consult the leaders of the Soviet party organizations on the spot.

Premises in which to issue instructions must be carefully prepared in advance, and their capacity, exits, entrances, and the possibility of strangers entering must be taken into consideration.

During the time instructions are issued the building must be securely guarded by the administrative workers.

In case anyone among those participating in the operations fail to appear for instructions, the county triumvirate should immediately take measures to substitute the absentee from a reserve force, which should be provided in advance.

The triumvirate through its representative should notify the officers gathered of the decision of the government to deport an accounted-for contingent of anti-Soviet elements from the territory of the respective republic or region. Moreover, a brief explanation should be given as to what the deportees represent.

Special attention of the (local) Soviet party workers gathered for instructions should be drawn to the fact that the deportees are enemies of the Soviet people and that, therefore, the possibility of an armed attack on the part of the deportees is not excluded.

3. Manner of Obtaining Documents

After the issuance of general instructions to the operative groups, they should definitely be issued documents regarding the deportees. Personal files of the deportees must be previously discussed and settled by the operative groups of townships and villages, so that there are no obstacles in issuing them.

After receiving the personal files, the senior member of the operative groups acquaints himself with the personal files of the family which he will have to deport. He must check the number of persons in the family, the supply of necessary forms to be filled out by the deportee, and transportation for moving the deportee, and he should receive exhaustive answers to questions not clear to him.

At the time when the files are issued, the county triumvirate must explain to each senior member of the operative group where the deported family is to be settled and describe the route to be taken to the place of deportation. Routes to be taken by the administrative personnel with the deported families to the railway station for embarkation must also be fixed. It is also necessary to point out places where reserve military groups are placed in case it should become necessary to call them out during possible excesses.

Possession and state of arms and ammunition must be checked throughout the whole operative personnel. Weapons must be completely ready for battle, loaded, but the cartridge should not be kept in the chamber. Weapons should be used only as a last resort, when the operative group is attacked or threatened with an attack, or when resistance is shown.

4. Manner of Executing Deportation

Should a number of families be deported from one spot, one of the operative workers is appointed senior in regard to deportation from the village, and his orders are to be obeyed by the operative personnel in that village.

Having arrived in the village, the operative groups must get in touch (observing the necessary secrecy) with the local authorities: chairman, secretary, or members of the village soviets; and should ascertain from them the exact dwelling of the families to be deported. After that the operative groups, together with the local authorities, go to the families to be banished.

The operation should be commenced at daybreak. Upon entering the home of the person to be banished, the senior member of the operative group should gather the entire family of the deportee into one room, taking all necessary precautionary measures against any possible excesses.

After having checked the members of the family against the list, the location of those absent and the number of persons sick should be ascertained, after which they should be called upon to give up their weapons. Regardless of whether weapons are surrendered or not, the deportee should be personally searched, and then the entire premises should be searched in order to uncover weapons.…

5. Manner of Separating Deportee from his Family

In view of the fact that a large number of the deportees must be arrested and placed in special camps and their families settled at special points in distant regions, it is necessary to execute the operation of deporting both the members of his family as well as the deportee simultaneously, without informing them of the separation confronting them. After having made the search and drawn up the necessary documents for identification in the home of the deportee, the administrative workers shall draw up documents for the head of the family and place them in his personal file, but the documents drawn up for the members of his family should be placed in the personal file of the deportee’s family.

The moving of the entire family, however, to the station should be done in one vehicle, and only at the station should the head of the family be placed separately from his family in a railway car specially intended for heads of families.

While gathering together the family in the home of the deportee, the head of the family should be warned that personal male articles are to be packed into a separate suitcase, as a sanitary inspection will be made of the deported men separately from the women and children.

At the stations the possessions of heads of families subject to arrest should be loaded into railway cars assigned to them, which will be designated by special operative workers appointed for that purpose.

6. Manner of Convoying the Deportees

It is strictly prohibited for the operatives convoying the vehicle-moved column of deportees to sit in the wagons of the deportees. The operatives must follow by the side and at the rear of the column of deportees. The senior operator of the convoy should periodically go around the entire column to check the correctness of movement.

The convoy must act particularly carefully in conducting the column of deportees through inhabited spots as well as in meeting passersby; they should see that there are no attempts made to escape, and no exchange of words should be permitted between the deportees and passersby.…

DEPUTY PEOPLE’S COMMISSAR OF STATE

SECURITY OF THE USSR

Commissar of State Security of the Third Rank

Signed: SEROVCORRECT: (Signed) MASHKIN 2

The forced-labor code quoted in a previous chapter indicates clearly that the MVD is in the business of supplying labor not only for its own enterprises but for other enterprises as well. It should not be concluded that the labor supply is given to other industries simply because they are in need. The MVD makes a profit from the “hiring out” of this labor.

To indicate how this commercial transaction was carried out in the Baltic States, the following extract from an NKVD telephonogram may serve.

Riga—Comrade Serov

Comrade Avakumov

Echelons from Latvia to proceed as follows: …

From Lithuanian SSR to the Altai Region: …

From the Estonian SSR:

37. Station Kotielnichi, Gorki Railway 1,600 persons 38. “

Shakhunya, “�?�? ” Kirov, “�?�? ” Slobodskoye, “�?�? ” Filonki, “�?�? ” Vekanskaya, “�?�? ” Murashi, “�?�? ” Orichi, “�?�? ” Yurya, “�?�? ” Koparino, “�?�? ” Pinyur, “�?�? ” Lusa, “�?�? ” 300 “ 39. “ 500 “ 40. “ 400 “ 41. “ 300 “ 42. “ 300 “ 43. “ 100 “ 44. “ 100 “ 45. “ 100 “ 46. “ 100 “ 47. “ 100 “ 48. “ 100 “ 49. “ Novosibirsk, Tomsk Railway 700 “ 50. “

Chany, “�?�? ” Kargat, “�?�? ” Promyshlennaya, “�?�? ” 1,000 “ 51. “ 1,000 “ 52. “ 1,000 “ 53. “ Starobielsk, Moscow-Donbass Railway

(Men only without their families)1,930 “ 54. “ Babynino, Moscow-Kiev Railway

(Men only without their families)1,000 “ 55. “ Solikamsk, Perm Railway

(Criminal offenders)472 “ Bills of lading to be prepared in accordance with above destinations.

Heads of the echelons to report progress once daily to Transport Department of the NKVD of the SSR.

(Signed) Chernyshev

Delivered: Kotliarev

Received: Vorobiev

June 13No. 30/5698/016

June 13, 1941

footnotes

1. See Appendices V and VI for a detailed breakdown of the deported Estonians during the first occupation.

2. This order of the NKVD (the Soviet Secret Police), and several other secret documents presented in this book, were secured by Lithuanian underground fighters, and were made available to the Commission of Inquiry into Forced Labor by the Lithuanian Information Center in New York City.

Appendix V

Persons executed in Estonia or deported from Estonia during first Soviet occupation, 1940–1941. This list, and that in Appendix VI, were supplied by the Estonian National Council, and are substantiated by Estonian Red Cross authorities.

| Men | Women | Total | |

| Arrested and deported to Russia | 5,451 | 525 | 5,976 |

| Arrested and executed in Estonia | 1,513 | 202 | 1,715 |

| Deported to Russia | 5,102 | 5,103 | 10,205 |

| “Conscripted” and deported to Russia | 33,304 | . . | 33,304 |

| Members of standing army, deported to Russia | 5,573 | . . | 5,573 |

| Deported to Russia in the exercise of their duties | 1,594 | 294 | 1,858 |

| Lost without trace | 782 | 319 | 1,101 |

| TOTAL | 53,319 | 6,413 | 59,732 |

| Disfigured corpses whose identity could not be ascertained | 228 | 7 | 235 |

Appendix VI

Estonians executed and deported during the first Soviet Occupation, 1940–1941, according to profession.

| Profession | Men | Women | Total |

| Agriculture | 14,565 | 1,720 | 16,285 |

| Industry | 16,185 | 1,158 | 17,343 |

| Transport and communications | 3,793 | 305 | 4,098 |

| Trade | 3,839 | 868 | 4,707 |

| Civil Service | 11,224 | 1,582 | 12,806 |

| Domestic work | 77 | 73 | 150 |

| Other professions | 426 | 153 | 579 |

| Profession unknown | 3,210 | 554 | 3,764 |

| TOTAL | 53,319 | 6,413 | 59,732 |

Digital discoveries

- Migliori Casino Online

- Casino Non AAMS

- Siti Casino

- Sites De Paris Sportifs Belgique

- Tous Les Sites De Paris Sportifs Belgique

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne Belgique

- Casino En Ligne Belgique Bonus

- I Migliori Casino Online

- Non Aams Casino

- Scommesse Italia App

- Migliori Casino Online Esteri

- Paris Sportif Crypto Sans Kyc

- Site De Paris Sportif

- Sweet Bonanza Avis

- Paris Sportif Ufc

- オンラインカジノ 出金早い

- Casino Live En Ligne Français

- Site De Paris Sportifs

- Meilleurs Nouveaux Casinos En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne Français

- Casino En Ligne

- Casino Retrait Instantané

- Casino En Ligne Fiable

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne 2026

- Casino En Ligne Retrait Immédiat

- Casino Français En Ligne

- Casino Italia Non Aams

- Casino Con Free Spin Senza Deposito

- Siti Di Scommesse Non Aams

- Migliore Casino Non Aams

- Casino Online Non Aams 2026

- 토토사이트 모음

- Top 10 Trang Cá độ Bóng đá

- Casino En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne France

- Casino En Ligne Argent Réel

- Casino En Ligne Retrait Immédiat 2026

- Nouveau Casino En Ligne 2026