“A Clear Provocation”

September 28, 2018

Esoteric Elements in Communist Language

In August of 1983, Andrei Berezhkov, the teen-aged son of a Soviet diplomat in Washington, apparently wrote a letter to President Reagan and another one to the New York Times in which he denounced the Soviet regime and asked for asylum in the United States. From press reports of the incident it would seem that the boy soon gave in to pressure from his father. Despite certain opportunities offered by American authorities, he hastily returned to the Soviet Union with his family. But before this denouncement there were some days of suspense during which both Soviet and American officials issued a variety of statements. By far the most interesting of these, to me, was reported by the New York Times (13 August):

“A Soviet Embasssy official, contending that the incident was a ‘clear provocation,’ said Thursday that the letters were forgeries.”

Provocation — what could the Soviet spokesman have meant? It is reasonable, from a Soviet point of view, to charge the Americans with forgery. It makes sense to charge them with a desire to score a propaganda point, whether or not the letters were genuine. But how could it conceivably be in the interest of the United States, no matter how dishonest, aggressive, or devious its officials might be, to “provoke” the Soviet Union in this instance? A charge of “provocation”, without any accompanying explanation, can only blunt and obscure the much more plausible (and therefore more potentially damaging) charge of forgery.

Less than a month after the Berezhkov case — on 1 September to be exact — a Soviet military airplane fired upon a civilian South Korean airliner and killed 269 people. The two cases had little similarity except for the language of the accompanying Soviet propaganda.

On 4 September the Soviet press agency TASS described the Korean flight as “a rude and deliberate provocation.” Two days later, a Soviet Embassy official in Ottawa declared it “a deliberate provocation” (Vancouver Sun, 7 September). In Moscow, 6 September, a lengthy TASS statement explained Soviet reasoning as follows:

“It was not a technical error [on the part of the Korean crew]. The plan was to carry out without a hitch the … intelligence operation but if it was stymied to turn all this into a political provocation against the Soviet Union.”

On 7 September Andrei Gromyko omitted any mention of intelligence gathering but again charged “provocation”:

“No matter who resorts to provocation of that kind, he should know that he will bear the full brunt of responsibility for it. … Those who today are still giving credence to [the American] falsehood will, no doubt, at long last understand the true aim of this major provocation. …”

Finally on 6 September Marshal Ogarkov, chief of the Soviet General Staff, conducted a press conference on the affair in Moscow. He charged a “deliberate, thoroughly planned intelligence operation”, but only after beginning his speech by charging a “provocation perpetrated by the US secret services.”

Elsewhere, pro-Moscow Communists spoke of both espionage and “provocation.” On 17 October, the New York Times reported from the United Nations that Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Cuba and Mongolia had all “defended the Soviet Union, saying that the airliner was a spy plane and represented a provocation by the United States.” William Kashtan, leader of the Canadian CP, declared that “The KAL incident … was an imperialist provocation.” Vancouver’s Communist Pacific Tribune of 19 October allowed itself a somewhat less formal style and said in an editorial that

“hysterical mesmerism is evidently the major stock-in-trade of imperialism these days … there was a load of provocative garbage about the USSR ‘knowing’ it was a 747 … Reagan-led hysteria, hate-peddling, provocation and boycotts eagerly lapped up by every stray dog of imperialism. …”

Those who read Communist propaganda habitually are of course inured and may not even notice that the use of “provocation” in these contexts, from a non-Communist point of view, is strange, illogical, and self-defeating.

Strange. Communist spokesmen are often attuned to current moods and fashions and can sound eminently reasonable to the Western ear. But there seems to be a sudden shift to the outlandish with an insistence on “provocation.” The effect on New York Times commentators like Serge Schmemann (14 September) and John F. Burns (11 September) may be taken as typical: they stumble over the word and put it between puzzled quotation marks.

Illogical. The Soviets charge that the Americans wanted to both “provoke” and to spy. But a spy defeats his purpose if he provokes his target into any sort of action. The TASS statement of 6 September tries to get around this conundrum by claiming to know a secret American plan to use the incident as “provocation” only if the espionage mission should fail. The difficulty here is that this is not a plausible plan for an intelligence operation and none of the other Soviet statements try to rationalise in this manner. Moreover, there is a further problem that demands explanation. If the American plan had been to “provoke”, and if the Soviets are so well aware of this American proclivity, why did they assist the American ploy by shooting at the plane? In other words if the whole thing was bait and the fish knew that it was bait, why did it bite?

Self-defeating. An argument is persuasive only if it is believable and coherent. To say that Americans are engaged in espionage against the Soviet Union is plausible; it is consistent with what most people know or suspect of the behaviour and the self-interest of modern governments. But to say that the Americans wish to “provoke” the Soviet Union is inconsistent with all such rational assumptions. There is no reason, at least no obvious reason, why Americans should wish to “provoke”, and any propaganda based on such allegation cannot be successful. Nevertheless, the Soviets and the pro-Soviet Communists persist in such allegations, usually without the slightest attempt to explain the puzzling irrationality with which they charge their opponents.

Nor is this new to Communist propaganda. The Red Army started its invasion of Finland on 30 November 1939. Twelve days before, TASS reported from Helsinki that “ruling circles in Finland [are] provoking war against the USSR.” The day before the invasion, on 29 November, a resolution of Moscow writers and poets solemnly expressed “indignation and anger that the Finns, prompted by the warmongers, have permitted wanton provocation.” The next day Molotov announced the invasion, declaring that “orders have been issued to the Red Army and Navy … to put an end to all Finnish provocations.” (The German-Soviet invasion of Poland, two months earlier, was not accompanied by such charges. Hitler merely complained that “the Polish nation refused my efforts for a peaceful regulation of neighbourly relations”, and the Soviets, then perhaps under Nazi influence, by and large limited their accusations against the Poles to that of “chauvinistic treatment of minorities”.)

***

How and why the Communists came to their fondness for “provocation” becomes clear enough once we take a look at the Russia of the late 19th century.

The various revolutionary groups (socialist, anarchist, populist) on the one hand, and the government’s secret police (the Okhrana) on the other, lived in an atmosphere of intrigue and conspiracy.

“Secrecy [Lenin wrote in 1902] is such a necessary condition for [our] kind of organisation that all the other conditions (number and selection of members, functions, etc.) must be made to conform to it.” [1]

Much of the secrecy had to do with spies which the revolutionary groups had in the police, and, more commonly, which the police had in the revolutionary organisations. Occasionally such agents entrapped (“provoked”) revolutionaries into actions for which the police would then arrest them. Such provocation soon became merged with simple espionage in the minds of the revolutionaries. By the 1890s all police spies in the Russian revolutionary movement were called “agents provocateurs” (provokatori) by the members of these movements.[2]

The Russian cognates of “provocation” and of the French “provocateur” (i.e. provokatsia and provokator) took on even broader meanings in the writings of Lenin. It is rare that he used either expression in the narrow sense — i.e. actual entrapment or provocation. Most frequently his usage relates to a suspected police spy or informer. Sometimes Lenin used such terms even more broadly, as very general pejoratives whose only connection to the original “provocation” is the allegation of deviousness. Thus, in a polemical reference to the Social Democratic founders of the Weimar Republic, he charged that “over 15,000 German Communists were killed as a result of the wily provocation and cunning manoeuvres of Scheidemann and Noske. …” [3]

There seems to be only one core idea that has remained with the term from beginning to end: a perception of a devious, conspiratorial enemy. But this idea is hidden to outsiders. To those to whom a “capitalist” world is engaged in a permanent conspiracy against the Soviet Union, and who see the need (as Lenin saw it) for a counter-conspiracy against these forces of darkness, the Communist usage of “provocation” becomes meaningful and natural. To everyone else the term must seem, as I have suggested, strange, illogical, self-defeating. It is a piece of esoterica, understandable only to the initiates.

***

Social scientists accept as a commonplace that there is some reciprocal influence between language and culture (although the exact nature of this relationship is under continuing debate). Consequently a number of writers have looked at Communist ideology by studying the Communists’ language.[4] But just about all of this literature has the crippling limitation of focusing on manifest ideology, on that which Communists profess.[5] These studies tell us about items like “proletariat”, “bourgeoisie”, “imperialism”, and so forth. Not one of them discusses “provocation” or other terms which form part of the non-professed or latent ideology.[6]

But it is most especially the latent ideology that needs to be studied. This is not easy. How do we know what a man believes in the absence of his own testimony? In general we must judge his actions more than his words. But his words too can be revealing of thoughts he may wish to hide. This is particularly so when these words seem odd, incongruous, and inconsistent with what he professes as his creed.

Many items of Communist vocabulary may serve both manifest and latent functions. One such item, in many ways a curiosity, is “red-baiting.” The expression has entered a number of American dictionaries in recent years, and is sometimes used by non-Communists who wish to make a point of being particularly liberal in respect to the rights of Communists. But generally its use is restricted to Communists and fellow-travellers. Moreover, unlike most other such technical Communist terms, there do not seem to be close equivalents in other languages.

My Unabridged Webster’s Dictionary defines “red-baiting” as “the act of baiting or harassing as a red often in a malicious or irresponsible manner.” [7] Not wishing harassment is of course a straightforward, perfectly understandable sentiment; but it constitutes only one — the manifest — meaning of the expression. An additional usage may be illustrated by the following very typical illustration.

In 1983, the Vancouver City Council contained four aldermen who prominently associated themselves with Communist causes, but only one of these was a professed Party member. When a letter to a local newspaper alleged all four to be Communists, one replied as follows: “There are no members of Council who belong to the Communist Party … [the first writer’s] approach to informing the public is red-baiting.” In this context, the term constitutes a complaint that a Communist is being identified as a Communist.

The resistance to such identification is the other — the latent — meaning of “red-baiting” that emerges from the contexts in which the phrase appears in the English-language Communist literature.[8] Since the 1920s, international Communism has distinguished itself from all other political movements by having a portion of its membership deny its political affiliation.[9] (I do not refer here to countries in which the Party is illegal.) This desire to hide its political identity — especially necessary for activity in front organisations — is part of the latent ideology of the Communist movement, and it is not surprising to find it reflected in what amounts to a piece of technical terminology.

One of the curious aspects of this usage is that, like “provocation”, it can only baffle the uninitiated. Sometimes the denial of Communist membership is transparently untruthful, as indeed it was in the Vancouver case. Moreover, from the point of view of the very outsider whom Communist propaganda wishes to influence, why should a Communist label be so vigorously resisted by Communist spokesmen? Doesn’t this invite the impression that it is shameful to be a Communist? Here again we see something that is strange to the outsider, illogical, and self-defeating to the Communist propagandist.

The term appears only in English although the camouflaging occurs everywhere. We don’t expect a one-to-one relationship between language and ideology,[10] but we might speculate on why the term is absent elsewhere: perhaps the small American and British Communist movements, lacking mass parties and mass followings, rely even more than those of the Continent on dissimulation, disguise, concealment. While Communists in France and Italy can get a respectful hearing under their own label, this is only barely possible in the English-speaking world. Perhaps the appearance of “red-baiting” as a term is related to the relative importance of the hidden when compared to the open Communist.

***

The interpretation of the latent content in Communist language, like that of dreams, can offer temptations for loose theorising. The exegeses I have offered so far — a Communist penchant for conspiracy, a Communist tendency toward disguise and dissimulation — are not very daring because there is ample non-linguistic evidence for them. But I wish to offer two final suggestions of a more speculative nature.

(1) Both “provocation” and “red-baiting” give the impression of a Communist who is acted upon rather than acting on his own responsibility. He is victimised (“baited”), and when he acts it is not because he wishes to but because he is pushed (“provoked”).[11]

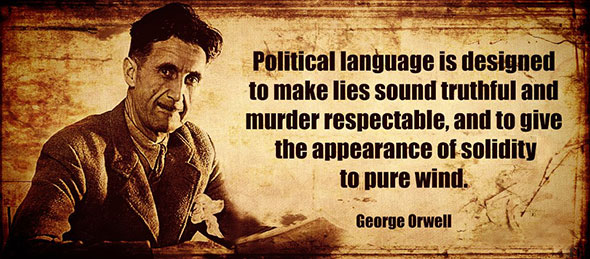

(2) The second suggestion is of an altogether different nature. I have tried to show that the Communist’s persistent use of technical vocabulary is related to latent ideology and strikes the outsider as strange, illogical, and self-defeating. Yet Communist propagandists persist in this usage, from the highest authorities in the Kremlin to the minor functionary in Canada. By doing so, I suggest, they give evidence that ideology, properly understood as including the latent, can take precedence over an opportunist desire to influence the Western public. Another way of putting this is that no matter how worldly-wise the Communists may be, they remain, at least to some extent, the prisoners of an irrational ideology that prevents them from any real communication with the rest of us.

Definitions

Western Communist Parties which want to make themselves “wide open to the masses” were criticised yesterday in a “Pravda” article by Mr Vadim Zagladin, deputy chief of the Kremlin’s International Information Department.

It appeared to be a response to last month’s congress of the Finnish Communist Party, at which moderate “Eurocommunists” ousted pro-Moscow hardliners from all leading posts.

Mr Zagladin said that recently in certain countries a feeling had arisen that strictly orthodox Leninist Communist parties were no longer needed. But this denied the class criteria of Communism, the fundamental principles of Marxism-Leninism, and the ideal of proletarian internationalism, he said.

In Soviet political language “proletarian internationalism” means unswerving loyalty to Moscow.

Mr Zagladin said the new type of Western Communist Party, “wide open to the masses,” was really a retreat to the old social-democratic model. Experience had shown that social-democratic parties could never bring about revolution or socialism. According to Lenin, a Communist party must be a “vanguard party” of tightly-disciplined activists leading the working masses.

Nigel Wade

reporting from Moscow

in the Daily Telegraph (London)

footnotes

[1] “What Is To Be Done?”, in Lenin, Collected Works, vol. 5, pp. 475-6.

[2] Ronald Hingley, The Russian Secret Police (1970), p. 81 and passim. For a discussion of the French and Russian background to the institution of agent provocateur, see James H. Billington, Fire in the Minds of Man (1980), pp. 470-1.

[3] “ ‘Left-Wing’ Communism — An Infantile Disorder,” in Lenin, Collected Works, vol. 31, p. 101.

[4] Some of the best work is in French. See especially Annie Kriegel’s incisive article “Langage et stratégie” in her Communismes au miroir français (1974). Other references are cited in Bernard Legendre, Le stalinisme français (1980), pp. 47-9. Some of the books in English are: Harry Hodgkinson, Doubletalk (1955); R. N. Carew Hunt, A Guide to Communist Jargon (1957); Michael Waller, The Language of Communism (1972); Tom Bottomore (ed.), A Dictionary of Marxist Thought (1983). The latter two volumes may be considered part of the Marxist apologetic literature.

[5] An exception is Arthur Koestler’s interesting story — in The God That Failed — of a young Communist girl who trapped herself by using the word “concrete” during a Gestapo interrogation.

[6] The distinction between “latent” and “manifest”, introduced to sociology by Robert Merton, has been used to refer to at least three distinct contrasts; the conscious and the unconscious; the intended and the not-intended; and the professed and the non-professed. Here I use only the last of these three.

[7] I was able to identify two of the three individuals whom the dictionary cites as using the term. One is Henry Wallace, one-time Democratic Vice-President of the United States who ran as Presidential candidate for the Communist-organised “Progressive Party” in 1948. The other is the much more obscure Joseph Barnes, a New York journalist, and Herald-Tribune editor, who had once appeared before the US Senate’s McCarren committee where he had been accused of (and had denied) a connection with Soviet Intelligence.

[8] A handy source is the volume The Fur and Leather Workers Union (1950) by the Communist historian Philip S. Foner, which gives an account of the Communist leadership of a trade union and deals with “red-baiting.”

[9] Perhaps the first prominent Communist who did this was also the founder of the first Communist front organisations, the German Willi Münzenberg. (Münzenberg later employed Arthur Koestler in Paris.) Afterwards he broke with the CP, and was mysteriously assassinated, apparently by the Soviet secret police. See David Pike, German Writers in Soviet Exile (1981).

[10] Discussion about the nature of the language-culture relationship tends to centre on the “Sapir-Whorf hypothesis.” For a balanced statement, see the article by Charles F. Hockett, “Chinese Versus English: An Exploration of the Whorfian Theses,” in Harry Hoijer (ed.), Language In Culture (1954).

[11] Just so is a man freed from feelings of guilt. Koestler has spoken of the Communist’s “blissfully clean conscience” when engaged in what others would consider wrong: in The God That Failed (ed. Richard Crossman. 1949), p. 33. A similar explanation has been advanced for the Rosenbergs’ consistent protestations of innocence in the face of overwhelming evidence that they were spies. See Ronald Radosh and Joyce Milton, The Rosenberg File (1983), pp. 340, 547.

Digital discoveries

- Migliori Casino Online

- Casino Non AAMS

- Siti Casino

- Sites De Paris Sportifs Belgique

- Tous Les Sites De Paris Sportifs Belgique

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne Belgique

- Casino En Ligne Belgique Bonus

- I Migliori Casino Online

- Non Aams Casino

- Scommesse Italia App

- Migliori Casino Online Esteri

- Paris Sportif Crypto Sans Kyc

- Site De Paris Sportif

- Sweet Bonanza Avis

- Paris Sportif Ufc

- オンラインカジノ 出金早い

- Casino Live En Ligne Français

- Site De Paris Sportifs

- Meilleurs Nouveaux Casinos En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne Français

- Casino En Ligne

- Casino Retrait Instantané

- Casino En Ligne Fiable

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne 2026

- Casino En Ligne Retrait Immédiat

- Casino Français En Ligne

- Casino Italia Non Aams

- Casino Con Free Spin Senza Deposito

- Siti Di Scommesse Non Aams

- Migliore Casino Non Aams

- Casino Online Non Aams 2026

- 토토사이트 모음

- Top 10 Trang Cá độ Bóng đá

- Casino En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne France

- Casino En Ligne Argent Réel

- Casino En Ligne Retrait Immédiat 2026

- Nouveau Casino En Ligne 2026